Chapter 4: Infant Perception and

Cognition

I. Methodologies used to assess infant perception

A.

Infant sucking

B.

Visual preference

C.

Habituation/dishabituation

1.

Operationalized as amount of time infant attends to stimuli – more familiar

stimuli receive less attention (see Figure 4-2)

2.

Habituation – decrease in response with familiarity

3.

Dishabituation (release from habituation) – resumption of response when stimulus

is changed

II.

The development of visual perception

A.

Vision in the newborn

1.

Can perceive light, but cannot accommodate for distance

2.

Can track but eyes do not converge and coordinate until about 6 months

3.

Acuity poor at birth, improves over 1st year (See Fig. 4-3)

4.

Color perception poor initially but improves by 8 weeks

B.

The development of visual preferences - prefer movement, high contrast,

symmetry, and curvature

C.

Psychological stimulus characteristics

1.

Kagan proposed that infants develop schemas around 2 months, and prefer to look

at things that deviate moderately (but not greatly) from their schema (See Fig.

4-7)

2.

This discrepancy principle may explain preference for novelty

3.

Early in processing infants prefer to look at the familiar, switching to

preference for novelty once a stable representation has been stored

D.

Development of face processing

1.

Neonates may have a weak bias to attend to faces over other stimuli (strengthens

over the first few months)

2.

How might this bias be explained by evolutionary processes?

3.

Infants prefer “facelike” over “non-facelike” stimuli (See Fig. 4-8)

III.

Auditory development

A.

Auditory ability improves over the first year, reaching maturity around 10 years

B.

Infants most sensitive to higher-pitches, can distinguish voices, and have

auditory preferences

C.

Speech perception

1.

Infants distinguish between phonemes similarly to adults

2.

Young infants can distinguish between phonemes from any language, but lose this

ability for all languages except the one(s) they hear over the first postnatal

year

3.

Can recognize frequently heard sound patterns by 4.5 months

IV.

Combining senses (intermodal integration)

A.

Infants are able to integrate sound and picture, preferring to watch pictures

with matching sound; also prefer match of their videotaped leg movements with

proprioceptive information (i.e., input from two senses that is consistent)

B.

Intermodal matching--Recognizing by one sense what has been perceived via

another sense

C.

Intersensory redundancy hypothesis

1.

Some stimuli provide information for more than one sense, such as the

co-occurring sound and sight of a bouncing ball.

Given experience with these intersensory redundant stimuli, babies begin

to attend to “amodal” properties of the stimuli (elements that are relevant to

multiple senses).

2.

Human and animal infants are prone to amodal information processing because it

unifies incoming sensory information; this helps them ignore irrelevant

information, leading to further development of perception, attention, and

cognition

V.

Infant cognition:

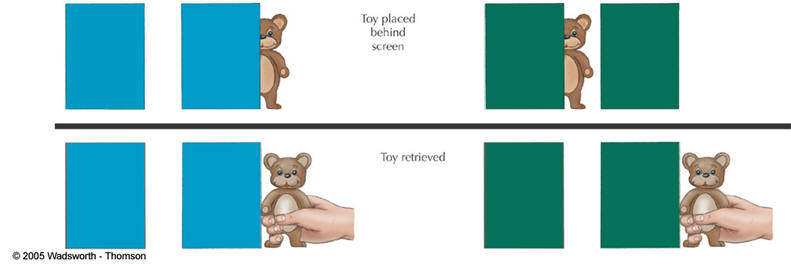

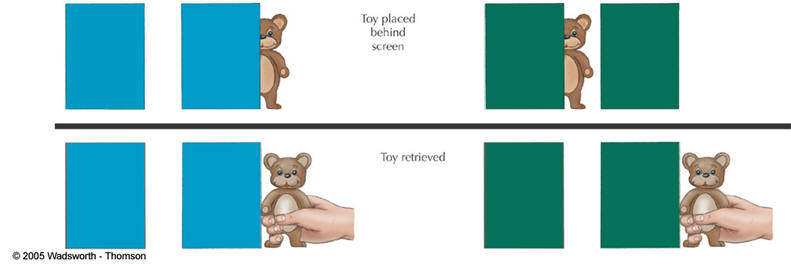

Violation-of-expectation method - infants look longer at events that

violate their expectations (physically impossible or “magical” events) of what

should happen

VI.

Core knowledge – babies are born with or quickly develop certain biases or

cognitive competencies of physical objects or events; common to all human

infants, and perhaps other species

A.

Object representation

B.

Object continuity and cohesion

1.

Object permanence

a.

Piaget

i.

object permanence first seen around 4 months, when baby will look for an object

if it is only partially covered

ii.

by 8 months can retrieve a hidden object, but still demonstrate the A-not-B

error

iii.

by 12 months can solve A-not-B tasks, but will not search for an object when it

has been moved from the place the baby expects it to be (invisible displacement)

iv.

true object permanence evident by 18 months

b.

More recent studies of object permanence

i.

the “violation of expectation” paradigm

ii.

looking time paradigm

c.

Findings vary depending on number of times sequence is viewed, or familiarity of

object (See Fig. 4-20)

Eight-month-old infants react with surprise when they see the impossible event staged for them. Their reaction implies that they remember where the toy was hidden. Infants appear to have a capacity for memory and thinking that greatly exceeds what Piaget claimed is possible during the sensorimotor period.

2.

Neo-nativist – infants are born with knowledge of object cohesion, continuity,

and contact

3.

architectural innateness for dealing with objects; processes are innate, not

knowledge

4.

Bogartz --infants are born with a domain-general set of mechanisms for

processing perceptual information; no innate object knowledge is needed

C.

Numerical representation

1.

Numerosity (determining number without counting) and ordinality (more than/less

than)

1.

Infants respond differently to arrays with different number of items

2.

10- to 12-month olds will choose box with more crackers, but only up to four

items; same pattern for rhesus monkeys

3.

6-month-olds can distinguish larger and smaller arrays of dots greater than 4,

but the difference in number of dots must be large

4.

This property also found for number of sounds

2.

Simple arithmetic

1.

5-month-olds appear to have rudimentary understanding of addition/subtraction

VIII.

Arguments against core knowledge

A.

Some argue that findings such as these can be explained without assuming innate

knowledge

B.

Current perception (what is seen now) can be compared to previously stored

perception (stored representation of earlier perception); increased looking time

at “novel” or “impossible” event due to increased processing time, and therefore

don’t require any innate understanding of physical properties

IX.

Category representation – to what extent are infants' categorical

representations similar to those of adults

A.

How measured – infants can habituate to a category just as they can habituate to

an individual stimulus

1.

Infants as young as 3 months can form perceptual categories

2.

The more exposure to the category the more finely they can discriminate category

members

3.

Categories formed can be as broad as mammals

4.

Categories likely based on perceptual similarities and experiences

B.

The structure of infants’ categories

1.

Infants appear to form a category prototype that can be used to identify new

category members (see Photo 4-3)

2.

However younger infants require stimuli that are typical, familiar to form a

category

X.

What is infant cognition made of

A.

Some of the apparent cognitive competencies seen in infants may be domain

specific (e.g. processing faces)

B.

Other types of skills may be domain general (e.g., understanding objects)

C.

Cognition of infants may not be qualitatively different from that of older

children; conceptual knowledge may coexist with sensorimotor processing

D.

Others suggest that rather than ask when a particular skill develops, ask about

the developmental sequence of a particular skill