|

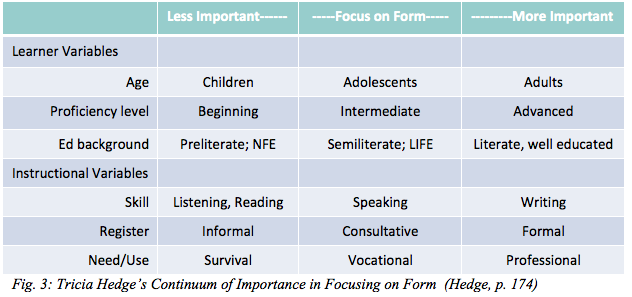

Implicit and Explicit Instruction Implicit and Explicit Instruction But the protestors aren’t done yet, asking, “Okay, I may teach students of various ages, but I don’t believe in explicit grammar instruction. Why should I study it?” To which the answer is that implicit grammar instruction is still a sort of grammar instruction. Teaching implicitly means the focus is on something other than grammar, but that doesn’t mean grammar is absent from the lesson. Grammar is inherently present any time the language is used, whether we pay attention to it or not and whether we ask students to pay attention to it or not. Knowing grammar gives you two choices, but not knowing gives you only one. If you know grammar, you can choose to focus on it or not. If you don’t know grammar, you don’t have a choice. You have to ignore it. Furthermore, teachers don’t always get to decide the curriculum, and they may find themselves in a context where the explicit teaching of grammar is required. A teacher who doesn’t know grammar is out of a job in these situations. In addition, specific tasks that ESL teachers are asked to do require metalinguistic knowledge of the language: 1) Analyzing student errors to identify areas for development, 2) Analyzing content area materials to determine appropriateness for ELLs at varying levels of proficiency, 3) Adopting/adapting materials for language level, not grade level content. The quotation above from the Minnesota standards for ELLs mentions the expectations of these types of tasks when it makes the statement about “instructional strategies” and “scaffolding of materials.” However, there is a great deal of merit in the point that teachers have options in whether or how much to focus on the form of language instead of its meaning. The protestations given shouldn’t be ignored altogether. It does matter whether the students are old or young, and it matters whether one is working on conversational language skill development or whether one is working on academic language skill development. Tricia Hedge cites Marianne Celce-Murcia’s ideas on the relationship between a focus on form and a number of learner and instructional variables and has drawn up a table to depict the relationships (see Fig. 4). The idea of focusing on the form of the language is viewed as a continuum of importance. One extreme is high importance in focusing on the grammatical or syntactic forms of the language, while the other extreme is low importance. Focusing on forms becomes more important as learners become older, more advanced in their language proficiency, and more well-educated. It also becomes more important as the situations for language use become more professional, more formal, and more frequently written. As focus on forms becomes more important, explicit instruction becomes more necessary.

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning Closely related to the issue of teaching implicitly or explicitly is, once the decision has been made to teach explicitly, whether one should present material so that students must follow an inductive thought process or a deductive thought process. When a person thinks inductively, he/she begins with a set of examples and draws a general conclusion that encompasses all the evidence in the examples. For example, a person might notice that trout have gills, that salmon have gills, and that barracuda have gills. These are all fish, so the person might come up with a general conclusion that all fish have gills. When a person thinks deductively, he/she begins with a general rule and uses it to work on a specific instance. To continue the fish example, once a person knows that all fish have gills, that person might look at a new creature, such as a dolphin, and look to see if it has gills to decide if it is a fish or not. Since dolphin doesn’t have gills, the person would conclude it is not a fish. This process of coming to a conclusion involves deductive reasoning. In the explicit teaching of grammar, teachers can decide whether to begin by giving a grammar rule and then giving students a series of sentences to work on that involve that rule or not. This would be explicit instruction with a deductive presentation. Another choice would be to give students a group of sentences and have them figure out what all the sentences have in common as far as form goes. The students then figure out the rule and the teacher lets them know whether they have come up with an accurate rule or not. This is explicit grammar instruction with an inductive presentation. Many teachers misunderstand an inductive presentation as implicit instruction. Inductive presentation is not implicit teaching, but it can act as a bridge for moving from implicit teaching to explicit teaching. It works well for people who have previously learned something implicitly to become conscious of what they already know. This is why it is frequently used in this course: the target population of learners is native speakers of English, and they have all learned English implicitly as very young children. |