|

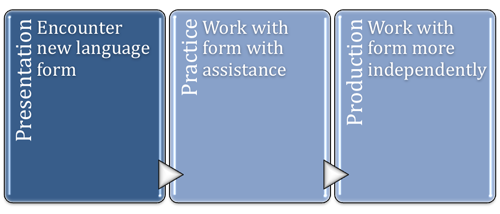

Making a Lesson Plan The Lesson Plan One key point to hold in mind is that a lesson plan is a tool to assist the teacher in the delivery of a lesson. It contains reminders of the plan in chronological order that a teacher can refer to during the delivery of the plan. As such, a plan can be highly detailed, much like a script for a play, or it can be more of an outline, a memory jogger rather than a script to read from. Just as essays and speeches share a typical form, having introduction, body, and conclusion, a lesson plan is often described in broad strokes. Language lessons often contain a presentation stage, a practice stage, and a production stage, in that order. In the presentation stage, the learners encounter the target language form, in the practice stage, they work with the form with assistance from the teacher, and in the production stage, they work with the language form largely independently.

Fig. 8 Stages in a language lesson In an inductive lesson, the students will encounter a language form in a meaningful context during the presentation stage, without a teacher providing technical explanations. The practice stage will expand the form beyond the initial context seen in the presentation, and the production stage may expand it further or may require students to work independently. At the end, there may be technical explanations of the form provided in the final stage so that the learner may have a reference to work with. In a deductive lesson, explanations of the form are provided in the presentation stage, and then the form is given in a new context in the practice and production stages, where the learners are freed further and further from referring to the explanations. One pitfall, especially when a deductive approach is taken, is for a teacher to spend more time explaining the syntactic form in technical terms than is given to providing practice opportunities and authentic use of the form for the learners. Grammar lessons for language learners needn’t be the same as the lessons a teacher had in college teacher education programs. In order to conceive of the importance of practice and production, one common perspective views the lesson structure as a pyramid (Fig. 9). Compare the weight in the deductive lesson plan given to the presentation stage, represented by the inverted pyramid on the left, to the one in the right-side-up pyramid on the right. Essentially, what often goes wrong is not focusing on form, but devoting too much time to the presentation of the form and not enough to the practice of it. Correct this common error, and a focus on form is helpful.

Fig. 9 Flipping the pyramid In the presentation phase of an inductive lesson, embed the grammatical form in a situation that it naturally occurs in. Constrain the situation so that the new form is the only new issue for the learners to deal with; this ensures that the learning load is manageable. This can be done by making the other elements in the situation familiar vocabulary words, other previously learned forms, and familiar situations either from real life or previous lessons. Use visual aids to concretize the situation. After deciding whether to use an inductive or deductive approach and deciding how this will affect the stages of the lesson plan, the details of the lesson plan can be prepared. In general, a teacher must consider the overall language proficiency level of the learners, what previous lessons have already covered, and how much of the new form can be covered in one lesson and how much must be put off until another day. Consideration of how much to cover and the order in which to cover the details is often called the scope (the issue of how much) and sequence (the issues of what order) of a lesson plan or a course curriculum. In order to include adequate amounts of practice and production, a teacher may find it necessary to cover less material than originally thought. For example, when considering teaching the verb BE in the simple present, a teacher might think primarily of the need to teach the agreement of the verb with the various possible subjects, that is, first, second, and third person both singular and plural. However, a teacher must also teach wh- question formation for subjects, wh- question formation for predicates, yes-no question formation, and short answers as well as the various verb complements: predicate adjectives, predicate nominatives, prepositional phrases, and adverbs of place & time. This is much more than can be covered in one 50-minute lesson period. The consideration of scope and sequence must include decisions about which of the above to teach first, which second, and so on. |