Psy

342 Learning & Memory

Chapter

4

Instrumental/Operant

Conditioning

A. Thorndike

The graph below is called a ______________

and summarizes how quickly cats learned to escape from a puzzle box.

Thorndike's measure of conditioning was _____?

Trial and error or insight?

For Thorndike’s cats, the behaviors that opened the door were followed by certain consequences: __________and____________.

As a result of these consequences, the cat became _____ likely to repeat the effective escape behaviors, which ultimately decreased the animal’s escape latency.

instrumental conditioning—an organism’s behavior changes because of the consequences that follow the behavior.

B. Skinner

Responsible for an enormous increase of interest in instrumental/operant conditioning in the 1940s and 1950s.

How did Skinner’s methods differ from Thorndike’s?

Discrete-trial procedure vs. free operant proceduresResponse latency vs. response rate

II. Behavior, Consequences, &

Contingencies

Instrumental/operant contingency:

Behavior

![]() Consequence (further, this

relationship is contingent)

Consequence (further, this

relationship is contingent)

A. Reinforcement & Punishment

reinforcement—the contingency that results when the consequence of a behavior causes the future probability of that behavior to INCREASE

Then what is a reinforcer?

punishment—the contingency that results when the consequence of a behavior causes the future rate of the behavior to decrease…

Then what is a punisher?

positive

reinforcement—when reinforcement involves the presentation of a stimulus

positive

punishment—when punishment involves the presentation of a stimulus

In this instance, positive does NOT mean __________.

negative

reinforcement—when the consequence in a reinforcement contingency is the removal of a stimulus

negative

punishment—when the consequence in a punishment situation is the removal of a

stimulus

In this instance, negative does NOT mean ___________.

4

key questions to help you determine the type of contingency involved.

B. How

might reinforcers and punishers serve an adaptive role in behavior?

C. Application

Operant conditioning in the treatment of alcohol abuse

One effective treatment for alcohol abuse is the community reinforcement approach (CRA) (Azrin, Sisson, Meyers, & Godley, 1982; Hunt & Azrin, 1973).

Explain the meaning and importance of the following statements:

(1) We define consequences and contingencies by their effects on behavior, not by

what we EXPECT their effects to be.

(2) If behavior is followed by a reinforcer, it is the behavior that is reinforced, not the organism.

(3) The contingent relationship between behavior and outcomes can lead to behaviors that do not appear to make sense.

II. Instrumental Conditioning Paradigms

Instrumental vs. Operant Distinction

A. Runways/Mazes

B. Escape & Avoidance

Paradigms

C. Operant Procedures

Bar-Press

Key-Peck

Human Operant Responses

Measuring Operant Responses—usually rate at which organisms emit response is the dependent variable in most operant conditioning studies

Cumulative recorder creates a record of __________________ as a function of time.

Shaping procedure

Reinforcement of behaviors that are closer and closer approximations of the target response

Application: The Lovaas treatment program (established in 1960's) uses operant conditioning principles to decrease problem behavior of autistic children and to increase the frequency of appropriate behaviors (e.g., language and social skills).

III. Positive Reinforcement Situations

Presentation of an event that increases

the probability of future behavior.

So responding is influenced mainly by

characteristics of the reinforcer.

A. Amount/Magnitude

Generally,

responding occurs faster and becomes more accurate as we increase the amount of

a reinforcer delivered after each response.

E.g.,

Crespi (1942)—5 groups of rats to run down a straight runway for food

IV:

# of food pellets in goal box (1, 4, 16, 64, or 256)

**Results:

After 20 trials, the running speeds of the groups corresponded directly to the

number of pellets received.

Complicating

factor—Some researchers have disagreed as to the definition of reinforcer

magnitude.

Several

studies have shown that if an experimenter gives two groups the same amount of

food for each response, but for one group the food is simply broken into more

pieces, the group receiving the most

pieces will respond faster.

**Quality

of reinforcement also matters.

We

can define quality by assessing how vigorously an organism consumes a reward

when it is presented.

High

quality reinforcers are consumed quickly by organisms, whereas low quality

reinforcers are consumed less quickly.

B. Delay of Reinforcement

Generally, the

longer that reinforcement is delayed after a response, the poorer the

performance of that response.

E.J.

Capaldi (1978)—Two

groups of rats received the same amount and quality of food reinforcement on

each trial.

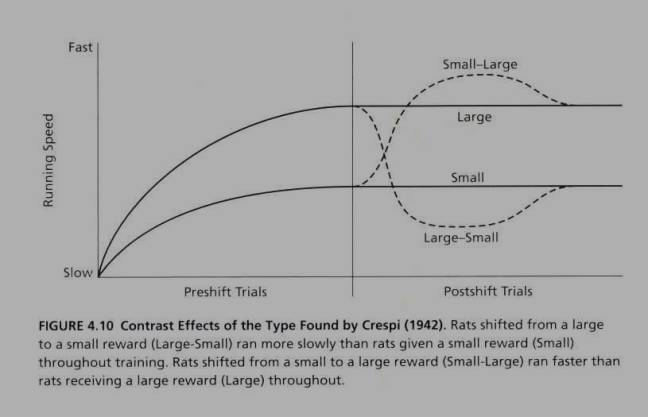

C. Contrast Effects—Effects

of quantity, quality, and delay of reinforcement on instrumental responding can

vary depending on an organism’s past experiences with a particular reinforcer.

Crespi

(1942)—Group 1 trained to traverse a runway for large amount of food, Group 2

for a small amount of food

After

several trials, the rats receiving the large reinforcer were running

consistently faster than the small-reinforcement group.

Then

switched half of the large-reinf. animals to the small reinforcer being given to

the other rats (large-small).

And

switched half the small-reinforcer rats to the large-reinforcer magnitude

(small-large).

D. Intermittent Reinforcement—Often, we can't reinforce each time an appropriate response is emitted.

What

is the effect of such reinforcement inconsistency on behavior?

It

is clear that instrumental learning is not dependent on continuous

reinforcement. In most species, instrumental responding develops quite

efficiently even when reinforcement occurs only intermittently.

Schedules of Reinforcement

Ratio

schedules—deliver reinforcer only after a certain number of

responses

Fixed Ratio (FR)

Variable Ratio (VR)

Fixed interval (FI)

Variable interval (VI)

Concurrent schedules—when more than one reinforcement schedule is operating at the same time

When

we are faced with choices between different schedules of reinforcement, how do

we respond?

Hernstein

(1961) measured the rate at which pigeons pecked keys that were associated with

different reinforcement schedules.

He

found that pigeons did NOT simply choose the key having the most favorable

schedule of reinforcement. That is, they did not make the vast majority of their

responses to the key that provided the most reinforcement in the shortest period

of time.

Instead,

pigeons divided their responses between the keys, and the rate of responding on

each key was directly related to the rate of reinforcement on that key.

As

a result, Hernstein proposed the matching law

The

formula for the matching law is:

![]()

IV. Negative Reinforcement Situations

A. Escape Learning

Amount of Reinforcement—In escape learning, the amount of reinforcement

corresponds to the degree to which the aversive stimulation is reduced after a

successful response.

Campbell

& Kraeling (1953)—exposed all rats to the same

shock intensity in the runway and reduced

this shock by varying degrees in the safe box.

That

is, all animals received shock reduction after responding, but most animals

still received SOME shock in the safe box.

The

speed of the escape response was a direct function of the degree to which shock

was reduced.

**Escape

learning depends more on the amount of negative reinforcement (degree to which

aversive stimulation is reduced) than on the intensity of the aversive stimulus

per se.

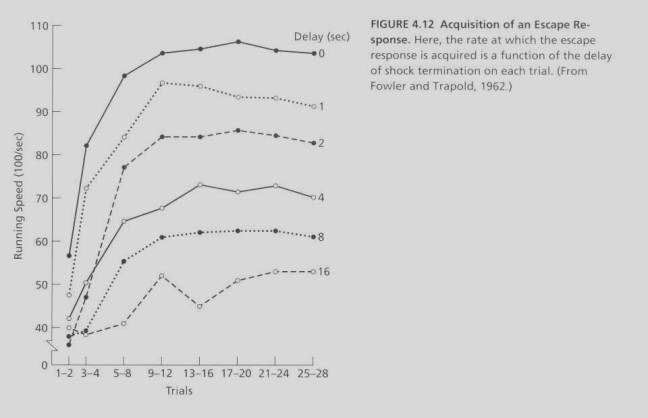

Delay

of Reinforcement—time

between the escape response and the reduction of the aversive stimulation.

Fowler

& Trapold (1962)—exposed rats to shock in an alleyway and required the

animals to run to a safe box to escape the shock.

The

delay in shock offset varied between 0 and 16 seconds.

Results-- escape speeds decreased as the delay of shock offset increased.

B. Avoidance Learning—A stimulus signals the presentation of the aversive

event. The organism must respond in the presence of the signal in order to avoid

the aversive event.

Two

stimuli—the signal and the aversive stimulus

The

characteristics of both of these stimuli are important determinants of avoidance

learning.

Intensity of Aversive Stimulus

Signal-Aversive Stimulus Interval--Avoidance

learning appears to occur most efficiently when the signal and the aversive

stimulus overlap, as is the case in a delayed-conditioning procedure.

Duration of the signal before onset of aversive event--In

general, signals of longer duration tend to facilitate the learning of the

avoidance response (Low & Low, 1962).

Termination of the Signal--Even when the organism’s response results in

avoidance of the aversive stimulus, the rate of learning depends on whether the

response also leads to the termination of the signal.

Kamin

(1957) conducted a two-way avoidance experiment using rats. All rats were able

to avoid shock by moving to the safe chamber during the signal-shock interval.

For one group, the signal terminated as soon as the avoidance response occurred

(o-second delay). In the other three groups, the signal ended either 2.5, 5, or

10 seconds after the avoidance response.

Punishment Situations (Read p. 118-122 for assign. 2)

Intensity & Duration of Punishment

Delay & Non contingent Delivery of Punishment

Responses Produced by the Punishing Stimulus

V. The Discriminative Stimulus

A

stimulus that is reliably present when a particular behavior is reinforced.

After

instrumental conditioning in the presence of a discriminative stimulus, the

presentation of that discriminative stimulus will increase the probability of

behaviors that have been reinforced in its presence….

Discriminative

stimuli make a behavior more probable, but ultimately they DO NOT CAUSE the

behavior to occur. It is the reinforcement contingency that controls the rate of

behavior.

VI. Extinction

Variables Affecting Extinction of Positively Reinforced Responses

Conditions Present During Learning

Conditions Present During Extinction

Variables Affecting Extinction of Negatively Reinforced Responses