“College is the best time of your life. When else are your parents going to spend several thousand dollars a year just for you to go to a strange town and get drunk every night?” -- Writer/humorist David Wood.

|

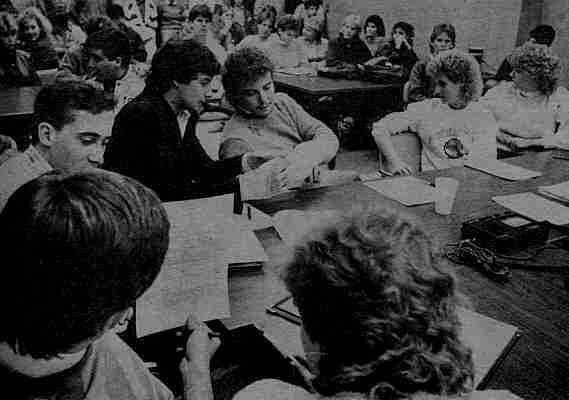

| 1985 -- MSU Student Senate hears complaints about a faculty member. |

No one can really pinpoint the first time that American educators complained that "students want to make demands on the school." Certainly words like this were voiced at Moorhead State well before the 1980s. Back in 1957, when students protested (covertly) over President Knoblauch's plan to use the 'student union' fund to build a bell carillon on the Moorhead State quad, they were acting in the manner of consumers -- they had raised the money to build a student union, so who was he to decide how to spend it? The 1960s were filled with student complaints about dormitory rules, meal choices, dress codes, and class choices; new programs in women's studies, humanities, and other subjects, were developed, in no small part due to students wanting them -- and making it clear that they would go to school elsewhere if their desires were ignored.

Before the 1980s, most students did not begin thinking about even going to college -- let alone which college -- before their last year of high school. But a study conducted in the early 1980s showed that by 1984 "41 percent of students decided to attend college as early as sixth grade and that, by ninth grade, 61 percent were certain about their decision to go to college." In 1987, a study released by Michigan State University found that 80 percent of students who subsequently enrolled in college "had decided to attend college by the end of their junior year in high school. Further, these students usually selected the school they attended from "a list" that they had complied over a period two or more years, and, for most, the geographic location of the college was no longer the deciding factor for the college they chose.

Thus, something new was happening in higher education -- students were becoming paying "customers" who did not hesitate to demand greater control over their learning. This was forcefully demonstrated at MSU, throughout the 1980s, in a grim, long-fought battle over the question of whether students should "have the right to evaluate their instructors." Requests by the Student Senate for faculty evaluations had begun in earnest in the 1950s. In 1956, President Knoblauch had formed a committee to consider how "student appraisal of faculty" could be developed. While the committee studied several publications on the subject and considered various methods for a system, no final plan emerged -- partly because the president preferred to maintain the prerogative for supervising faculty and the faculty were by 1958 at loggerheads with the president over how the college should be managed.

The subject of student evaluations of faculty simmered along through the 1960s, no only at MSC but around the nation. In the absence of formal systems through which students could comment about faculty classroom performance, students at some schools developed their own, informal systems. Cheaply printed "Class Guides" (sometimes called "Rap Sheets") circulated among students at such schools as Harvard, Dartmouth, Yale, and the larger state universities, which contained comments about faculty and frequently contained movie-like ratings (1 to 5 stars). The faculty at these schools invariably responded that ratings guides were pointless because education "is not a popularity contest." Some departments, however, created forms that faculty could voluntarily use with students in their classes; the results were thus uneven.

In the early 1970s, administrations at each of the Minnesota state colleges were working to develop a uniform system for student evaluations; the evaluations issue was added to the negotiations that began when state university faculty won the right to form a labor union. Thereafter, the Inter Faculty Organization contract contained the formal procedure by which faculty performance was measured for tenure and promotion. It would not be until a decade later that a uniform evaluation was agreed on during contract renegotiations. That moment marked a victory for students after three decades of effort. The system still exists (see a copy of the current evaluation form here).

Student choice now influences everything from the kinds of food on campus (fast food outlets, brands of coffee, pop, etc.) to the timing of semester breaks. The days when colleges could act "in loco parentis" (as parents) over the students were gone -- if it ever really existed. Students had by the 1980s made it clear that they had learned Aristotle's cardinal lesson:

Note: Statistics and detail on how contemporary students select colleges are drawn from Jillian Kinzie, Don Hossler, et. al., Fifty Years of College Choice: Institutional Influences on the Decision-Making Process (2004).