I. The

Elasticity of Demand

A. Definition of elasticity:

B. The Price

Elasticity of Demand and Its Determinants

1. Definition of price elasticity of demand:

2.

Determinants of the Price Elasticity of Demand

a.

Availability of Close Substitutes: the more substitutes a good has, the more

elastic its demand.

b. Necessities

versus Luxuries: necessities are more price inelastic.

c.

Definition of the market: narrowly defined markets (ice cream) have more elastic

demand than broadly defined markets (food).

d. Time

Horizon: goods tend to have more elastic demand over longer time horizons.

C. Computing

the Price Elasticity of Demand

1. Formula

![]()

2. Example: the

price of ice cream rises by 10% and quantity demanded falls by 20%.

Price

elasticity of demand = (20%)/(10%) = 2

3. Because

there is an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded (the price

of ice cream rose by 10% and the quantity demanded fell by 20%), the price

elasticity of demand is sometimes reported as a negative number. We will ignore

the minus sign and concentrate on the absolute value of the elasticity.

D. The Midpoint

Method:

1. Because we

use percentage changes in calculating the price elasticity of demand, the

elasticity calculated by going from one point to another on a demand curve will

be different from an elasticity calculated by going from the second point to the

first. This difference arises because the percentage changes are calculated

using a different base.

a. A way

around this problem is to use the midpoint method.

b. Using the

midpoint method involves calculating the percentage change in either price or

quantity demanded by dividing the change in the variable by the midpoint between

the initial and final levels rather than by the initial level itself.

c.

Example: the price rises from $4 to $6 and quantity demanded falls from 120 to

80.

% change in price = (6

- 4)/5 × 100% = 40%

% change in quantity

demanded = (120-80)/100 = 40%

price elasticity of

demand = 40/40 = 1

E. The Variety

of Demand Curves

1.

Classification of Elasticity

a. When the

price elasticity of demand is greater than one, demand is defined to be elastic.

b. When the

price elasticity of demand is less than one, the demand is defined to be

inelastic.

c. When

the price elasticity of demand is equal to one, the demand is said to have unit

elasticity.

2. In general,

the flatter the demand curve that passes through a given point, the more elastic

the demand.

3.

Extreme Cases

a. When the

price elasticity of demand is equal to zero, the demand is perfectly inelastic

and is a vertical line.

b. When the

price elasticity of demand is infinite, the demand is perfectly elastic and is a

horizontal line.

![]()

F.

Total Revenue and the Price Elasticity of Demand

1. Definition

of total revenue: the amount paid

by buyers and received by sellers of a good, computed as the price of the good

times the quantity sold.

2. If demand is

inelastic, the percentage change in price will be greater than the percentage

change in quantity demanded.

a. If price

rises, quantity demanded falls, and total revenue will rise (because the

increase in price will be larger than the decrease in quantity demanded).

b. If price

falls, quantity demanded rises, and total revenue will fall (because the fall in

price will be larger than the increase in quantity demanded).

3. If demand is

elastic, the percentage change in quantity demanded will be greater than the

percentage change in price.

a. If price

rises, quantity demanded falls, and total revenue will fall (because the

increase in price will be smaller than the decrease in quantity demanded).

b. If price

falls, quantity demanded rises, and total revenue will rise (because the fall in

price will be smaller than the increase in quantity demanded).

G. Elasticity

and Total Revenue along a Linear Demand Curve

1. The slope of

a linear demand curve is constant, but the elasticity is not.

a. At points

with a low price and a high quantity demanded, demand is inelastic.

b. At points

with a high price and a low quantity demanded, demand is elastic.

2. Total

revenue also varies at each point along the demand curve.

I. Other

Demand Elasticities

II. The Elasticity of Supply--Again in the book, but not on the test. Focus on the HW problems.

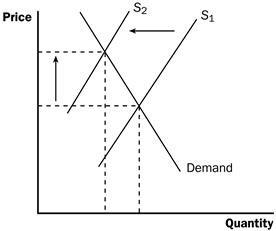

III. Three Applications of

Supply, Demand, and Elasticity

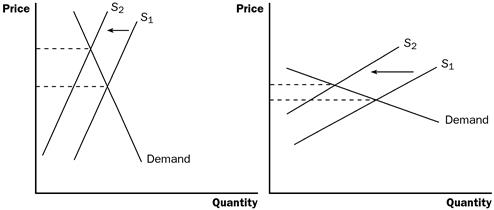

A. Can Good

News for Farming Be Bad News for Farmers?

1. A new hybrid

of wheat is developed that is more productive than those used in the past. What

happens?

2. Supply

increases, price falls, and quantity demanded rises.

3. If demand is

inelastic, the fall in price is greater than the increase in quantity demanded

and total revenue falls.

4. If demand is

elastic, the fall in price is smaller than the rise in quantity demanded and

total revenue rises.

5. In practice,

the demand for basic foodstuffs (like wheat) is usually inelastic.

a. This means

less revenue for farmers.

b. Because

farmers are price takers, they still have the incentive to adopt the new hybrid

so that they can produce and sell more wheat.

c. This

may help explain why the number of farms has declined so dramatically over the

past two centuries.

d. This may

also explain why some government policies encourage farmers to decrease the

amount of crops planted.

B. Why Did OPEC

Fail to Keep the Price of Oil High?

1. In the 1970s

and 1980s, OPEC reduced the amount of oil it was willing to supply to world

markets. The decrease in supply led to an increase in the price of oil and a

decrease in quantity demanded. The increase in price was much larger in the

short run than the long run. Why?

2. The demand

and supply of oil are much more inelastic in the short run than the long run.

The demand is more elastic in the long run because consumers can adjust to the

higher price of oil by carpooling or buying a vehicle that gets better mileage.

The supply is more elastic in the long run because non-OPEC producers will

respond to the higher price of oil by producing more.

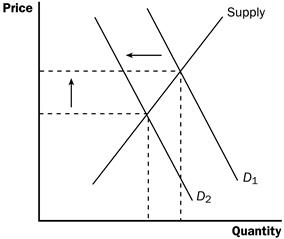

C. Does Drug

Interdiction Increase or Decrease Drug-Related Crime?

1. The federal

government increases the number of federal agents devoted to the war on drugs.

What happens?

a. The supply

of drugs decreases, which raises the price and leads to a reduction in quantity

demanded. If demand is inelastic, total expenditure on drugs (equal to total

revenue) will increase. If demand is elastic, total expenditure will fall.

b. Thus,

because the demand for drugs is likely to be inelastic, drug-related crime may

rise.

2. What happens

if the government instead pursued a policy of drug education?

a. The demand

for drugs decreases, which lowers price and quantity supplied. Total expenditure

must fall (because both price and quantity fall).

b. Thus, drug

education should not increase drug-related crime.

I. What

Are Costs?

A. Total

Revenue, Total Cost, and Profit

1. The goal of

a firm is to maximize profit.

2. Definition of total revenue:

![]()

3. Definition of total cost:

4. Definition of profit:

![]()

B. Costs as

Opportunity Costs

1. The cost of

something is what you give up to get it.

2. The costs of

producing an item must include all of the opportunity costs of inputs used in

production.

3. Total

opportunity costs include both implicit and explicit costs.

a. Definition of explicit costs:

b. Definition of implicit costs:

c. The

total cost of a business is the sum of explicit costs and implicit costs.

d. This is the

major way in which accountants and economists differ in analyzing the

performance of a business.

e. Accountants

focus on explicit costs, while economists examine both explicit and implicit

costs.

D. Economic Profit versus Accounting Profit

Definition of economic profit:

a. Economic

profit is what motivates firms to supply goods and services.

b. To

understand how industries evolve, we need to examine economic profit.

3. Definition of accounting profit:

4. If implicit

costs are greater than zero, accounting profit will always exceed economic

profit.

II. Production and Costs

A. The

Production Function

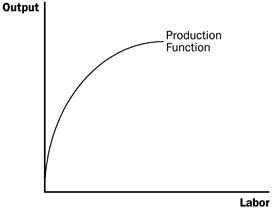

1. Definition of production function:

2. Example:

Caroline's cookie factory. The size of the factory is assumed to be fixed;

Caroline can vary her output (cookies) only by varying the labor used.

|

Number

of Workers |

Output |

Marginal

Product of Labor |

Cost of

Factory |

Cost of

Workers |

Total

Cost of Inputs |

|

0 |

0 |

--- |

$30 |

$0 |

$30 |

|

1 |

50 |

50 |

30 |

10 |

40 |

|

2 |

90 |

40 |

30 |

20 |

50 |

|

3 |

120 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

60 |

|

4 |

140 |

20 |

30 |

40 |

70 |

|

5 |

150 |

10 |

30 |

50 |

80 |

|

6 |

155 |

5 |

30 |

60 |

90 |

3. Definition of marginal product:

a. As the

amount of labor used increases, the marginal product of labor falls.

b. Definition

of diminishing marginal product:

4. We can draw

a graph of the firm's production function by plotting the level of labor (x-axis)

against the level of output (y-axis).

a. The slope

of the production function measures marginal product.

b. Diminishing

marginal product can be seen from the fact that the slope falls as the amount of

labor used increases.

B. From the

Production Function to the Total-Cost Curve

1. We can draw

a graph of the firm's total cost curve by plotting the level of output (x-axis)

against the total cost of producing that output (y-axis).

a. The total

cost curve gets steeper and steeper as output rises.

b. This

increase in the slope of the total cost curve is also due to diminishing

marginal product: As Helen increases the production of cookies, her kitchen

becomes overcrowded, and she needs a lot more labor.

III. The Various Measures

of Cost

Fixed and Variable

Costs

1. Definition of fixed costs:

2. Definition of variable costs:

![]()

3. Total cost is equal to

fixed cost plus variable cost.

|

Output |

Total

Cost |

Fixed

Cost |

Variable

Cost |

Average

Fixed Cost |

Average

Variable Cost |

Average

Total Cost |

Marginal

Cost |

|

0 |

$3.00 |

$3.00 |

$0 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

1 |

3.30 |

3.00 |

0.30 |

$3.00 |

$0.30 |

$3.30 |

$0.30 |

|

2 |

3.80 |

3.00 |

0.80 |

1.50 |

0.40 |

1.90 |

0.50 |

|

3 |

4.50 |

3.00 |

1.50 |

1.00 |

0.50 |

1.50 |

0.70 |

|

4 |

5.40 |

3.00 |

2.40 |

0.75 |

0.60 |

1.35 |

0.90 |

|

5 |

6.50 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

0.60 |

0.70 |

1.30 |

1.10 |

|

6 |

7.80 |

3.00 |

4.80 |

0.50 |

0.80 |

1.30 |

1.30 |

|

7 |

9.30 |

3.00 |

6.30 |

0.43 |

0.90 |

1.33 |

1.50 |

|

8 |

11.00 |

3.00 |

8.00 |

0.38 |

1.00 |

1.38 |

1.70 |

|

9 |

12.90 |

3.00 |

9.90 |

0.33 |

1.10 |

1.43 |

1.90 |

|

10 |

15.00 |

3.00 |

12.00 |

0.30 |

1.20 |

1.50 |

2.10 |

C. Average and

Marginal Cost

1. Definition of average total cost:

2. Definition of average fixed cost:

3. Definition

of average variable cost:

4. Definition of marginal cost:

![]()

5. Average

total cost tells us the cost of a typical unit of output and marginal cost tells

us the cost of an additional unit of output.

D. Cost Curves

and Their Shapes

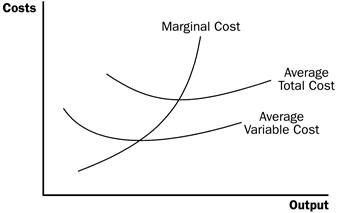

1. Rising

Marginal Cost

a. This occurs

because of diminishing marginal product.

b. At a low

level of output, there are few workers and a lot of idle equipment. But as

output increases, the coffee shop gets crowded and the cost of producing another

unit of output becomes high.

2. U-Shaped

Average Total Cost

a. Average

total cost is the sum of average fixed cost and average variable cost.

![]()

b.

AFC declines as output expands and

AVC typically increases as output

expands. AFC is high when output

levels are low. As output expands, AFC

declines pulling ATC down. As fixed

costs get spread over a large number of units, the effect of

AFC on

ATC falls and

ATC begins to rise because of

diminishing marginal product.

c.

Definition of efficient scale:

the quantity of output that minimizes average total cost.

3. The

Relationship between Marginal Cost and Average Total Cost

a. Whenever

marginal cost is less than average total cost, average total cost is falling.

Whenever marginal cost is greater than average total cost, average total cost is

rising.

b. The

marginal-cost curve crosses the average-total-cost curve at minimum average

total cost (the efficient scale).

4. Typical Cost

Curves

a. Marginal

cost eventually rises with output.

b. The

average-total-cost curve is U-shaped.

c. Marginal cost crosses average total cost at the minimum of average total cost.

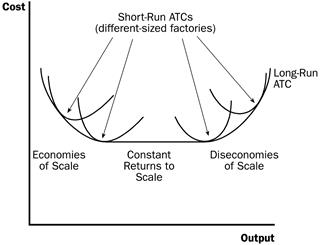

IV. Costs in the

Short Run and in the Long Run

A. The division

of total costs into fixed and variable costs will vary from firm to firm.

B. Some costs

are fixed in the short run, but all are variable in the long run.

1. For example,

in the long run a firm could choose the size of its factory.

2. Once a

factory is chosen, the firm must deal with the short-run costs associated with

that plant size.

C. The long-run

average-total-cost curve lies along the lowest points of the short-run

average-total-cost curves because the firm has more flexibility in the long run

to deal with changes in production.

D. The long-run

average-total-cost curve is typically U-shaped, but is much flatter than a

typical short-run average-total-cost curve.

E. The length

of time for a firm to get to the long run will depend on the firm involved.

F. Economies

and Diseconomies of Scale

1. Definition of economies of scale:

2. Definition of diseconomies of scale:

3. Definition of

constant returns to scale: