John Brown Legacy Lesson Plan

By Brian Krause

TAH Grant 2009-2010

Timetable: 2-3 class

periods

Grades: High School

Objectives: For

students to dig deeper and gain a better understanding of John Brown,

the raid on Harper’s Ferry, VA, and the subsequent end to John Brown’s

life and the legacy that followed.

Materials Needed –

The following primary source materials:

*Brantz

Mayer Visit to Harper’s Ferry

*John

Brown to Mass. Legislature

*John

Brown Song

*NY

Tribune article on execution

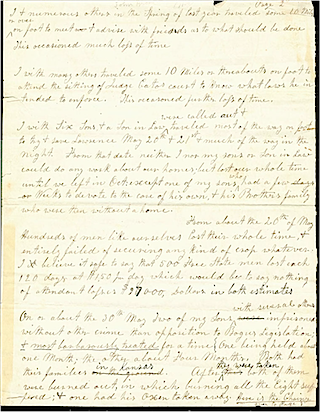

*Free

State Kansas Fund

*John

Brown to NY Tribune 1857

*John

Brown Southern Reaction

*State

Aide for Kansas

*Independent

Democrat Articles on the Raid

*John

Brown Brief Letters

*John

Brown to Mary Ann Brown 1859

Also

needed: poster board, colored pencils, rulers

Lesson Description:

1.)

Class will be divided into groups of 5 students or smaller

2.)

Each group will be given copies of the above primary source documents

3.)

Each group will look at the documents by first having each student read at

least 2 of the primary source documents and then teaching what they

have learned about the documents to other members of the group

4.)

After students are familiar with all of the information in the documents an

entire class discussion will be held to check for understanding and

answer any questions/fill in any gaps in student understanding

5.)

Students will then be creating a 10-slide storyboard on John Brown’s life

showing the progression of events in his life and the reaction that was

seen after his execution, students will also include their thought as to

whether John Brown was a hero or a villain and why – each group member will be

responsible for creating at least 2 of the slides

6.)

Groups will present storyboards to the rest of the class when completed

Assessment: Students

will be graded based on a rubric consisting of group

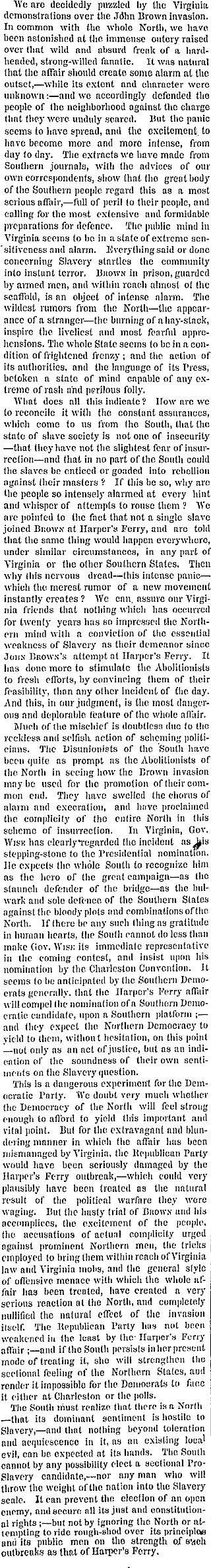

John Brown Legacy Documents

Brantz Mayer Visit to Harpers Ferry,

1856

“The Potomac, at this

point, is a third of a mile wide, and foams over a bed of ledges crossing it at

right angles like so many fractured barriers, denoting the conflict between the

ridge and river when it burst through the hills. Such, with few intermissions,

is the character of scenery from the Point of Rocks to Harper’s Ferry, which is

built on a narrow, declivitous tongue, lying directly in the confluence of the

Shenandoah and Potomac, and washed on either side by those noble streams. The

railway reaches it by a stupendous curving bridge of nine hundred feet over the

latter; and as the mountain steeps converge precipitously at all points about

the gap, but small space is left for building with accessible convenience.

Nearly all the level river-margin has been used for the National Armory, so

that the town scrambles picturesquely among the upland bluffs, till the

hill-top, like the end of all things, is terminated by the groves and monuments

of a cemetery.

Our first visit was

to the Armory, where we were introduced to all the mysteries in this wonderful

assemblage of contrivances for death. Every thing was exhibited and set in

motion—from the ponderous tilt-hammers, which weld steel into solidity, down to

the delicate operations by which the impulse of a hair can put these terrible

engines in action. I was soon struck by the fact that, after all, it is not so

easy to kill a man—especially, if we consider the intricate preparations which

have to be made in constructing weapons for human slaughter. We learned that a

musket consists of forty-nine pieces, and that the number of operations in

completing one—each of which is separately catalogued and valued—amount to

three hundred and forty-six; all, in some degree, requiring different trades

and various capacities for execution; so that, perhaps, no man, or no two men

in the establishment, could perform the whole of them in manufacturing a

perfect weapon!

I confess that, with

but little turn for mechanical science, most of these complicated machines were

rather surprising than comprehensible to me; so that, while my companions

strolled through the apartments in quest of instruction, I followed leisurely

in their rear, rather grieving than glorying in the inventive skill that had

been lavished on their construction under national auspices. It may be

considered more sentimental than practical in the present belligerent state of

mankind, to doubt the wisdom of making military preparations under the amiable

name of “defense,” yet I have never been able to understand why it

should not be “constitutional” to create as well as to kill, and to make a

sickle as well as a sword! Why it is that political law allows millions for the

belongings of war, and denies a dollar to those genial arts which, in ten

years, would do more for the progress of humanity than centuries of traditionary

force have effected for its demoralization? Nay, how much more beneficially

would these hundreds of workmen be employed, if government devoted their labor

to the manufacture of such unpicturesque instruments as hoes, spades, rakes,

axes, pitchforks, plows, and reaping machines; and if the army, which is to

wield the perilous weapons that are strewn in every direction, were transmuted,

under national patronage, into cultivators of those “homesteads” which

politicians so cheaply vote them! But, alas! the soldier is epic, and the

farmer only pastoral, and pageantry beats homeliness all the world over!

These lackadaisical

fancies floated through my mind as I walked over the half mile or armory; and I

hope I may not be set down as “too progressive” or “Utopian,” if I divulge them

in this public confessional.

It was noon when we

left the Armory and climbed to the fragment of Jefferson’s Rock, which affords

the best coup d’oeil of this celebrated scenery. It was a fatiguing

tramp under a mid-day sun, but we found a breeze singing down the gorge of the

Shenandoah when we rested under the old pine-tree among the cliffs. The rock

itself is of very little interest, except for its association with Mr.

Jefferson’s name, and its remarkable poise on a massive base. The drawing at

the beginning of this article presents an accurate view of the whole scene.

From the gap between the fragments the prospect combines the grand and

beautiful in a wonderful degree. Beyond the brow of the hill very little of the

town is seen to disfigure the original features of the prospect, so that the

wilderness of mountain, forest, and water may still be as freshly enjoyed as

they were by the earliest travelers. Indeed it is impossible for language to

sketch the spirit of the spot more vividly than is done in the bold penciling

of Jefferson. “You stand,” says he, “on a very high point of land; on your

right comes up the Shenandoah, having ranged the foot of the mountain a hundred

miles to seek a vent; on your left approaches the Potomac in quest of a passage

also. In the moment of their junction they rush together against the mountain,

rend it asunder, and pass off to the sea.” In a few distinct words of outline

we have the geology and geography of the spot before us; but when the sun is

lower and the shadows broader than at the time of our visit, so as to impart

variety of tone and effect to the scene, it is difficult to conceive a wilder

prospect than the mountains forming the gap, or a more placid landscape than

that which waves away beyond it, till hill, forest, and river fade in the east.

There is a remarkable contrast between the roughness of the foreground and the

pastoral quiet of the distance, so that the very landscape seems to teach the

need and harmony of repose after struggle.

Source: Extract from Brantz Mayer. "A June Jaunt," Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, April 1857.

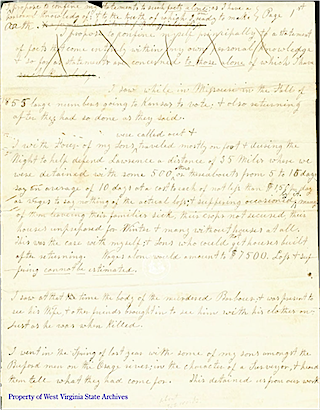

John Brown to Mass. Legislature

John Brown to Mary Ann Brown

November

8, 1859

Charlestown Jefferson

Co. Va:

8th Nov 1859

Dear Wife &

Children Every One

I will begin by

saying that I have in some degree recovered from my wounds; but that I am yet

quite weak in my back & sore about my left Kidney. My appetite has been

quite good for most of the time since I was hurt. I am supplied with almost Every

thing I could desire to make me comfortable, and the little that I do lack

(some few articles of clothing which I lost) I may perhaps soon get again. I am

besides quite cheerful having (as I trust) the peace of God which passeth all

understanding" to "rule in my heart" and the testimony (in some

degree) of a good conscience that I have not lived altogether in vain. I can

trust God with both the time and the manner of my death; believing as I now do

that for me at this time to seal my testimony (for God & humanity) with my

blood, will do vastly more toward advancing the cause I have Earnestly

Endeavored to promote, than all I have done in my life before. I beg of you all

meekly and quietly to submit to this; not feeling yourselves to be in the least

degraded on that account. Remember dear wife and children all, that

Jesus of Nazareth suffered a most Excruciating death on the cross as a felon -

under the most aggravating circumstances. Think also of the prophets, and

apostles and Christians of former days, who went through greater tribulations

than you or I: and (try) to be reconciled. May God Almighty comfort all your

hearts, and soon wipe away all tears from your eyes. To him be endless praise.

Think too of the crushed millions "who have no comforter." I charge

you all - never (in your trials) to forget the griefs "of the

poor that cry and of those that have none to help them." I wrote most

Earnestly to my dear and afflicted wife not to come on for the present

at any rate. I will now give you my reasons for doing so. First it would

use up all the scanty means she has or is at all likely to have to make herself

and children comfortable hereafter. For let me tell you that the sympathy that

is now aroused in your behalf may not always follow you. There is but little

more of the romantic about helping poor widows and their children than there is

about trying to relieve poor "niggers." Again the little

comfort it might afford us to meet again, would be dearly bought by the pains

of final seperation [sic]. We must part, and I feel assured; for us to

meet under such dreadful circumstances would only add to our distress. If she

comes on here she must be only a gazing stock throughout the whole journey, to

be remarked upon in every look, word and action by all

sorts of creatures and by all sorts of papers throughout the whole

country, again it is my most decided judgement that in quietly and submissively

staying at home vastly more of generous sympathy will reach her; without

such dreadful sacrifice of feeling as she must put up with if she comes on. The

visits of one or two female friends that have come on here have produced great

Excitement which is very annoying: and they cannot possibly do me any good. O

Mary do not come, but patiently wait for the meeting (of those who love God

and their fellow men) where no seperation [sic] must follow. "They shall

go no more but forever" - I greatly long to hear from some one of you, and

to learn any thing that in any way affects your welfare. I sent you $10. the

other day; did you get it? I have also endeavored to stir up Christian friends

to visit you and write to you in your deep affliction. I have no doubt that

some of them at least will heed the call. Write to me, care of Capt. John Avis,

Charlestown Jefferson Co. Va: "Finally my beloved be of good

comfort." May all your names be "written in the Lambs book of

life" - May you all have the purifying and sustaining influence of the

Christian religion - is the Earnest prayer of your affectionate husband and

Father.

John Brown

P. S. I cannot

remember a night so dark as to have hindered the coming day: nor a storm so

furious or dreadful as to prevent the return of warm sunshine and a cloudless

sky. But beloved ones do remember that this is not your rest; that in

this world you have no abiding place or continuing city. To God and his

infinite mercy I always commend you.

Ever Yours

J. B.

To the Friends of Freedom.

New York Tribune

March 4, 1857

The undersigned,

whose individual means were exceedingly limited when he first engaged in the

struggle for liberty in Kansas, being now still more destitute, and no less

anxious than in time past to continue his efforts to sustain that cause, is

induced to make this earnest appeal to the friends of freedom throughout the

United States, in the firm belief that his call will not go unheeded. I ask all

honest lovers of liberty and human rights, both male and female, to hold up my

hands by contributions of pecuniary aid, either as counties, cities, towns,

villages, societies, churches, or individuals. I will endeavor to make a

judicious and faithful application of all such means as I may be supplied with.

Contributions may be sent in drafts to W. H. D. Callender, cashier State Bank,

Hartford, Conn. It is my intention to visit as many places as I can during my

stay in the States, provided I am first informed of the disposition of the

inhabitants to aid me in my efforts, as well as to receive my visit. Information

may be communicated to me (care of Massasoit House) at Springfield, Mass. Will

editors of newspapers friendly to the cause kindly second the measure, and also

give this some half-dozen insertions? Will either gentlemen or ladies, or both,

who love the cause, volunteer to take up the business? It is with no little

sacrifice of personal feeling that I appear in this manner before the

public.

JOHN BROWN.

Source: F. B. Sanborn, ed., The Life and Letters of John

Brown. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1891., pp. 379-80

The John Brown Song (courtesy of West Virginia State Archives)

New York Semi-Weekly Tribune

December

6, 1859.

JOHN BROWN’S EXECUTION.

THE EXECUTION OF CAPT. BROWN

From Our Special

Correspondent.

Baltimore, Dec. 3, 1859.

Telegraphing from

Charlestown or Harper’s Ferry to The Tribune being out of the question, I am

forced to lose a day and write from this place. The execution was in the

highest degree imposing and solemn, and without disturbance of any kind. Lines

of patrols and pickets encircled the field for ten miles around, and over five

hundred troops were posted all about the gallows. At 7 o’clock in the morning

workmen began to erect the scaffold, the timber having been hauled the night

previous. At 8 troops began to arrive. Troopers were posted around the field at

fifty feet apart, and two lines of sentries further in. The troops did not form

hollow around the gallows, but were so disposed as to command every approach.

The sun shone brightly, and the picture presented to the eye was really

splendid. As each company arrived it took its alloted position. On the easterly

side were the cadets, with their right wing flanked by a detachment of men with

howitzers; on the northeast, the Richmond Grays; on the south, Company F of

Richmond; on the north, the Winchester Continentals, and, to preserve order in

the crowd, the Alexandria Rifleman and Capt. Gibson’s Rockingham Company were

stationed at the entrance gate, and on the outskirts. At 11 o’clock the

procession came in sight, and at once all conversation and noise ceased. A dead

stillness reigned over the field, and the tramp of the approaching troops alone

broke the silence. The escort of the prisoner was composed of Capt. Scott’s

company of cavalry, one company of Major Loring’s battalion of defencibles,

Capt. Williams’s Montpelier Guard, Capt. Scott’s Petersburg Grays, Company D,

Capt. Miller, of the Virginia Volunteers, and Young Guard, Capt. Rady, the

whole number the command of Col. T. P. August, assisted by Major Loring–the

cavalry at the head and rear of the column.

The prisoner sat upon

the box which contained his coffin, and, although pale from confinement, seemed

strong. The wagon in which he rode was drawn by two white horses. From the time

of leaving jail until he mounted the gallows stairs he wore a smile upon his

countenance, and his keen eye took in every detail of the scene. There was no

blenching nor the remotest approach to cowardice or nervousness. His remarks

have not been correctly reported in the Baltimore and New-York papers. As he

was leaving jail, when asked if he thought he could endure his fate, he said,

“I can endure almost anything but parting from friends; that is very hard.” On

the road to the scaffold, he said, in reply to an inquiry, “It has been a

characteristic of me from infancy not to suffer from physical fear. I have suffered

a thousand times more from bashfulness than from fear.” On entering the field

he said, as if surprised, “I see all persons are excluded from the field except

the military.” I was very near the old man, and scrutinized him closely. He

seemed to take in the whole scene at a glance, and he straightened himself up

proudly, as if to set to the soldiers an example of a soldier’s courage. The

only motion he made, beyond a swaying to and fro of his body, was that same

patting of his knees with his hands that we noticed throughout his trial and

while in jail. As he came upon an eminence near the gallows, he cast his eyes

over the beautiful landscape and followed the windings of the Blue Ridge

Mountains in the distance. He looked up earnestly at the sun and sky, and all

about, and then remarked, “This is a beautiful country. I have not cast my eye

over it before–that is, while passing through the field.” The cortege passed

half around the gallows to the east side, where it halted. The troops composing

the escort took up their assigned position, but the Petersburg Grays, as the

immediate body guard, remained as before, closely hemming in the prisoner. They

finally opened ranks to let him pass out, when, with the assistance of two men,

he descended from the wagon, bidding good by to those within it; and then, with

firm step and erect form, he strode past Jailor, Sheriff, and officers, and was

the first person to mount the scaffold steps. He then looked about him,

principally in the direction of the people, in the far distance. Then to Capt.

Avis, his jailor, he said, “I have no words to thank you for all your kindness

to me.” To Sheriff Campbell he remarked, “Let there be no more delay than is

necessary.” His black slouched hat was then removed, his elbows and ankles were

pinioned, and the white hood was drawn over his head. The Sheriff requested him

to step forward on the trap. He said, “You have put this thing over my head and

I cannot see; you must lead me.” There are eight minutes of suspense, while the

stupid cavalry are trying to find their proper position. Impatient at the

delay, Col. Scott gives the signal, Sheriff Campbell severs the rope with his

hatchet, the trap falls with a horrid screech of its hinges, and the

unfortunate man swings off into the air.

There was but one

spasmodic effort of the hands to clutch at the neck, but for nearly five

minutes the limbs jerked and quivered. He seemed to regain an extraordinary

hold upon life. One who had seen numbers of men hung before told me [he] had

never seen so hard a struggle. After the body had dangled in mid air for twenty

minutes, it was examined by the surgeons for signs of life. First the

Charlestown physicians went up and made their examination, and after them the

military surgeons, the prisoner being executed by the civil power and with

military assistance as well. To see them lifting up the arms, now powerless,

that once were so strong, and placing their ears to the breast of the corpse,

holding it steady by passing an arm around it, was revolting in the extreme.

And so the body

dangled and swung by its neck, turning to this side or that when moved by the

surgeons, and swinging, pendulum like, from the force of the south wind that

was blowing, until, after thirty-eight minutes from the time of swinging off,

it was ordered to be cut down, the authorities being quite satisfied that their

dreaded enemy was dead. The body was lifted upon the scaffold and fell into a

heap as limp as a rag. It was then put into the black walnut coffin, the body

guard closed in about the wagon, the cavalry led the van, and the mournful

procession moved off.

Throughout the whole

sad proceeding the utmost order and decorum reigned. I think that when the

prisoner was on the gallows, words in ordinary tones might have been heard all

over the forty-acre field. In less than fifteen minutes the whole military

force had left the field of execution, a dozen sentries alone, perhaps,

remaining. The townspeople having been kept at a considerable distance, and

none from the country about being allowed to approach nearer than a mile, there

were not, I think, counting soldiers and civilians, more than a thousand

spectators. A great felling of exasperation prevails in consequence of this

foolish stringency, and it is a wonder than conflicts have not arisen between

the citizens and their protectors.

John Brown, although

at times willing to argue with the local clergy upon religious matters, has

absolutely rejected all appearance of spiritual comfort at their hands, even

maintaining that those who were capable of countenancing Slavery, were not fit

to come between him and his God. The other day, he said, that instead of any

clergyman of Charlestown, if they would suffer him to be followed to the place

of execution by a family of little negro children, headed by a pious slave

mother, it would be all he would ask. The New-York Herald reports him to

have said when told that his wife could not remain with him more than three or

four hours, “I want this favor from the State of Virginia.” This is incorrect,

for with the same contemptuous independence which he has ever displayed, he

said, proudly, “Oh, I don’t ask any favors of the State of Virginia, You must

do your duty.” When the husband and wife parted, she shed some tears, but the

old hero, patting her on the shoulder, said, “Mary, this is not right. Show

that you have nerves.” She is said to have straightened herself up as if

electrified, and wept no more. The body left Charlestown under escort in the afternoon,

and at Harper’s Ferry was delivered up to Mrs. Brown.

Like a string that

snaps after great tension, the public mind at Charlestown seemed relieved the

moment that the body had been returned to the jail. The extra sentries were

called in, and people were suffered once more to pass in and out of town with

tolerable freedom. The dread is not all removed yet, however, for every night

mysterious lights are seen to shoot up, in the direction of Harper’s Ferry, which

are answered elsewhere. Despite all vigilance and search, no cause can be

assigned, and it is, therefore, believed that parties of rescuers are patiently

biding their time to take revenge, when fancied security once more prevails. It

is said that there can be no shadow of doubt that large bodies of armed men

have been hovering very near to Charlestown, and the remaining prisoners are

guarded with the most jealous vigilance. Yesterday morning orders were issued

that no more visitors shall be admitted to the prisoners, they having implored

the authorities to give them their little remaining time for reflection.

Independent Democrat Articles

on John Brown Raid

October

25, 1859

DARING ABOLITION FORAY!

OUTRAGEOUS ATTEMPT TO ABDUCT SLAVES FROM JEFFERSON COUNTY,

VIRGINIA.

The Soil of Virginia Stained with the blood of her Citizens

in Attempting to Defend their Firesides from Rapine and Robbery.

THE INFERNAL DESPERADOES CAUGHT, AND THE VENGEANCE OF AN

OUTRAGED COMMUNITY ABOUT TO BE APPEASED.

About midnight of

Sunday John Brown, with his force amounting, as they say, to 22 crossed the

Potomac Bridge with a one-horse covered wagon, containing their guns, picks

&c. They immediately seized Patrick Higgins, the watchman at the Bridge,

who gave one of the party a blow and made his escape, informing the Conductor

of the night train of Cars, Capt. Phelps. They then endeavored to induce

Hayward, the free colored watchman of the Railroad Office to take up arms and

join them in their nefarious purposes. Upon his refusing to do so, they

immediately shot him. He was a valuable fellow, whose life was worth more than all

the bandit, as he was trusted with everything in the Depot.

Sixteen of them

taking possession of the Armory and Arsenal, the others repaired to the

residence of Col. L. W. Washington, near Halltown, in this county, and after

arousing him from his bed, with pointed rifles, demanded his surrender, and

that of his negroes, &c. From thence they proceeded to the residence of Mr

John H. Alstadtt, living on the turnpike, and made a similar demand. They then

returned to Harpers Ferry, and placed their captives in the Government

Watchhouse.

The insurgents having

cut the telegraph wires, and stationed themselves at various points prevented

further entrances in the public square. Mr. Thomas Burley, being seen with a

gun was shot by a negro sentinel from the corner of one of the Arsenal

buildings. The ball passed through is body killing him almost instantly. This negro

fellow was afterwards shot.

Capt. John Avis of

this town formed a company of 20 men who were posted in front of the Arsenal. Capt.

Botts was detached with 20 volunteers, who took possession in front of the

“Galt House,” in the rear of the Arsenal. Capt. Rowan’s Guards crossed the

Potomac River and took possession of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Bridge.

The citizens of the place, without any regular command, took other stations of

the town, thereby cutting off all retreat.

The firing then

commenced. Capt. Avis forced the door of the Arsenal with a gun taken from the

hands of Mr. Leonard Sadler, of this town, one of the Soldiers of 1812. The

fire becoming too warm, the insurgents fled to the watch house. Before they

abandoned the Arsenal ground, and before the charge was made upon them, George

W. Turner, Esq., one of our most estimable and valuable citizens, was shot as

he was passing down High street. He died in a short time afterwards.

The citizens made

gallant charges at both works of the Armory. At the Rifle Factory the rebels

were driven into the river. One was taken prisoner and three shot. A negro man

of Col. Washington was drowned in his effort to escape. He had been forced to

take up arms.

Thus having been

driven from every point, they were virtually whipt, as none were left but those

in the watch house, who were anxious to capitulate as they were hemmed up and

cut off from every avenue of escape. Their terms of capitulation were that they

should be allowed to pass over the Bridge into Maryland with their arms. The

response of our officers was an unconditional surrender.

The insurgents had

made holes in the watch house, from which points they fired. Fontaine Beckham, Esqr,

Agent of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and Mayor of Harpers Ferry, was

killed. He was on the Railroad in front of the house. About 5 o’clock the

Winchester Contine[n]tal Guards Capt B. B. Washington arrived, and were

stationed to guard the upper works. A train of cars from Frederick brought

three companies, about 100 strong.

In the morning of

Tuesday, about 3 [o]’clock, the military of Baltimore, with the Marine from

Washington, arrived so that in 28 hours from the time of alarm we had on the

ground 10 companies, numbering upwards of 400, and one company of regulars, 75

strong, besides 1500 citizens. The Alexandria Riflemen, were also present on

Tuesday.

On Tuesday morning,

Col. Lee stormed the Watch house. One of the Marines was killed, and one

slightly wounded. All the insurgents were either killed or wounded.

Out of the whole 22

as stated all have been killed or taken prisoners except Cooke and Taylor.

The negroes, who were

captured from our citizens, as soon as an opportunity was presented, made their

escape, and returned to their masters much gratified to be able to do so. It is

gratifying to know that there is not one of our negroes who would voluntarily

take up with these desperadoes

We give below the list

of those who were taken prisoners of the marauding party:--and who are now in

the Charlestown Jail—

Capt. John Brown, of

New York;

Aaron D. Stevens of Con.

Edwin Coppeck, Iowa.

Shields Green (colored) of Harrisburg Pa.

John Copeland (colored) of Obe[r]lin, Ohio.

The following is a

description of the assault upon the Engine house, as published in the Baltimore

American, whose reporter was eye-witness of the scene:

Shortly after 7

o’clock, on Tuesday morning, Lt. J. E. B. Stuart of the 1st Cavalry, who was

acting as aid for Col. Lee, advanced to parley with the besieged, Samuel

Strider, Esq., bearing a flag of truce. They were received at the door by Capt Brown—Lieut

Stuart demanded an unconditional surrender, only promising them protection from

immediate violence, and trial by law. Capt. Brown refused all terms but those

previously demanded, which were substantially: “That he should be permitted to

march out with his men and arms, taken their prisoners with them; that they

should proceed unpursued to the second toll-gate, when they were free their

prisoners. The soldiers were then at liberty to pursue and they would fight if

they could not escape.” Obviously this was refused and Lieut Stuart pressed

upon Brown his desperate position, and urged a surrender. The expostulation

though beyond ear-shot, was evidently very earnest, and the coolness of the

Lieutenant and the courage of his aged flag bearer, won warm praise.

At this moment the

interest of the scene was intense. The volunteers were arranged all around the

building, cutting off escape in every direction. The marines divided in two

squads, were ready for a dash at the door. Finally, Lieut. Stuart, having

exhausted all argument with the determined Capt. Brown, walked slowly from the

door. Immediately the signal for attack was given, and the Marines headed by

Col. Harris and Lieut. Green advanced in two lines on each side of the door.

Two powerful fellows sprang between the lines and with heavy sledge hammers

attempted to batter down the door. The door swung and swayed, but appeared to

be secured with a rope, the spring of which deadened the effect of the blows.

Failing thus to obtain a breach, the marines were ordered to fall back, and

twenty of them took hold of a ladder, some forty feet long and advancing at a

run, brought it with tremendous force against the door. At the second blow it

gave way, one leaf falling inward in a slanting position. The marines

immediately advanced to the breach, Major Russell and Lieut. Green leading. A

marine in the front fell; the firing from the interior was rapid and sharp,

they fired with deliberate aim, and for the moment the resistance was serious

and desperate enough to excite the spectators to something like a pitch of

frenzy. The next moment the marines poured in, the firing ceased, and the work

was done, whilst the cheers rang from every side, the general feeling being

that the marines had done their part admirably.

Note: Copy of article is in John Brown Scrapbook, Boyd Stutler,

folder 7, Boyd B. Stutler Collection, West Virginia State Archives.

John Brown's Last Prophecy

Charlestown, Va, 2nd, December, 1859

I John Brown am now quite

certain that the crimes of this guilty,

land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as

I now think: vainly flattered myself that withought very much

bloodshed; it might be done.

(John Brown's last

letter, written on day he hanged. From "John Brown: a Biography," by

Oswald Garrison Villard.)

![]()

Letter from Mahala Doyle

Altho' vengeance is not mine, I confess that I do feel gratified to hear that

you were stopped in your fiendish career at Harper's Ferry, with the loss of

your two sons, you can now appreciate my distress in Kansas, when you then and

there entered my house at midnight and arrested my husband and two boys, and

took them out of the yard and in cold blood shot them dead in my hearing. You

can't say you done it to free slaves. We had none and never expected to own

one...My son John Doyle whose life I beged of you is now grown up and is very

desirous to be at Charlestown on the day of your execution.

(A letter sent to John

Brown while in jail. From "To Purge This Land with Blood" by Stephen

Oates.)

![]()

Letter from Frances Ellen

Watkins

Nov. 25, 1859

Dear Friend: Although the hands of Slavery throw a barrier between you and me,

and it may not be my privilege to see you in the prison house, Virginia has no

bolts or bars through which I dread to send you my sympathy...I thank you that

you have been brave enough to reach out your hands to the crushed and blighted

of my race. You have rocked the bloody Bastille; and I hope from your sad fate

great good may arise to the cause of freedom...

(A letter from Frances

Watkins, a free black living in Kendallville, Indiana. From "Freedom's

Unfinished Revolution," by William Friedheim and The American Social

History Project.)

![]()

A Plea for Capt. John

Brown

By Henry David Thoreau

I am here to plead his cause with you. I plead not for his life, but for his

character, - his immortal life; and so it becomes your cause wholly, and is not

his in the least. Some eighteen hundred years ago Christ was crucified; this

morning, perchance, Captain Brown was hung. These are the two ends of a chain

which is not without its links. He is not Old Brown any longer; his is an angel

of light.

(Read to the citizens of

Concord, Mass., Sunday Evening, October 30, 1859.)

![]()

Richmond "Whig"

Newspaper Editorial

Though it convert the whole Northern people, without an exception, into

furious, armed abolition invaders, yet

old Brown will be hung! That is

the stern and irreversible decree, not only of the authorities of Virginia, but

of the PEOPLE of Virginia, without a dissenting voice. And, therefore,

Virginia, and the people of Virginia, will treat with the contempt they

deserve, all the craven appeals of Northern men in behalf of old Brown's

pardon. The miserable old traitor and murderer belongs to the gallows,

and the gallows will have its own

(Richmond

"Whig" newspaper editorial quoted in the "Liberator", Nov.

18, 1859. From "John Brown: a Biography," by Oswald Villard)

![]()

John Brown Writes From

Jail

Charlestown, Jefferson County, VA, Nov. 1, 1859

My Dear Friend E. B. of R. I. :

You know that Christ once armed Peter. So also in my case, I think he put a

sword into my hand, and there continued it, so long as he saw best, and then

kindly took it from me. I mean when I first went to Kansas. I wish you could

know with what cheerfulness I am now wielding the "Sword of the

Spirit" on the right hand and on the left. I bless God that it proves

"mighty to the pulling down of strongholds." I always loved my Quaker

friends, and I commend to their kind regard my poor, bereaved widowed wife, and

my daughters and daughters-in-law, whose husbands fell at my side. One is a

mother and the other likely to become so soon. They, as well as my own

sorrow-stricken daughter[s], are left very poor, and have much greater need of

sympathy than I, who, through Infinite Grace and the kindness of strangers, am

"joyful in all my tribulations."

Your friend,

John Brown

(From "John Brown: a Biography," by Oswald Villard)

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/brown/filmmore/reference/primary/index.html

John Brown and Southern Politics.