Chris Stroup

Teaching American History on the Great

Plains

Summer 2010 - Lesson Plan 2

Class: CIHS America History 1301

Reconstruction

Objective:

For

students to expand their understanding of the politics, struggles, and

shortfalls of putting the United States back together after the American Civil

War. Students will examine various

aspects of the time period to determined what were the greatest struggles and

accomplishments of the time period.

Procedure:

Over the

course of two days students will be exposed to a series of materials that will

provide information on Reconstruction of the United States following the

American Civil War. There are multiple

resources available to the students, and they must utilize four, and from these

be able and prepared to defend their assigned position on Reconstruction. Oral

arguments will follow in class.

Resources:

A.

America: A

Narrative History. 6th Edition.

Tindahl and Shi, 2004. Pg 714-735

- Text excerpt explaining the period of Reconstruction

B. Smartboard projection of three main

Reconstruction plans (summaries) (attached)

C. “President Andrew Johnson Denounces

Changes in His Program of Reconstruction,

1867”

(From Major Problems in American History: Vol. 1 to 1877 - by Elizabeth Cobbs-Hoffman,

Jon Gjerde)

- President

Johnson presents his argument against franchisement of blacks and his opposing

radical reconstruction, which might lead to blacks in the South governing

whites – and his fear of this.

D. “Congressman Thaddeus Stevens

Demands a Radical Reconstuction” (From Major

Problems

in American History: Vol. 1 to 1877 - by Elizabeth Cobbs-Hoffman, Jon Gjerde)

- Stevens’

argument for radical reconstruction, and his politically motivated reasons

behind it.

E. “United States Atrocities”

(excerpt) (From Major Problems in American History: Vol.

1 to 1877 - by Elizabeth Cobbs-Hoffman,

Jon Gjerde)

Ida

B. Wells

- Wells

brings forth the problems faced by the African American community after

slavery, including that very little was accomplished during Reconstruction.

F. “DuBois’ Niagara Address,

1906” (excerpt) (From Major Problems in American

History: Vol. 1 to 1877 - by Elizabeth Cobbs-Hoffman, Jon

Gjerde)

- Dubois

presents a list of problems facing the African American community, and how in

actuality Reconstruction did little for blacks.

G. The Unfinished Nation-Tattered Remains(Downloaded from Learn360)

A clip

from the full video: The Unfinished

Nation

This

clip shows the cultural dynamics taking place between White southerners and

former slaves right after the Civil War, as well as providing information on

the corruption in the state governments.

Grade: 9-12| ©2004, Intelecom.

H.

Reconstruction: Northern Disagreement [08:31] (Downloaded from

Learn360)

A clip from the full video: Reconstruction: The Struggles Of Ordinary People

Following

election dispute, this clip examines the Northerners not only not embracing the

idea of African-American equality, but finally backing off and left African

Americans to sink or swim on their own in the South.

Grade: 9-12| ©2004, PBS.

I.

Freedom: A History of US: Episode 7: What Is Freedom? (Downloaded

from

Learn360)

A clip

from the full video: Freedom: A History

of US: Episodes 5 - 8

An

overview of the post Civil War period, providing information on early attempts

to heal, challenges of/for freed slaves, and a look at Plessy v Ferguson.

Grade: 6-8, 9-12| ©2002, PBS.

J.

Just the Facts: America's Documents of Freedom 1868-1890 [29:20]

(Downloaded from Learn360)

This

short video presents and interprets the documents following the American Civil

War and how they helped/hindered in the healing.

Grade: 6-8, 9-12| ©2003, Cerebellum.

K.

Reconstruction: The Beginning [19:36] (Downloaded from Learn360)

A clip

from the full video: Reconstruction: The

Second Civil War: Retreat

Abraham

Lincoln's first speech following the Civil War described how the fight of

Reconstruction was only beginning. Learn how African Americans struggled to

claim their freedom and claim their civil rights in a nation that was wrestling

with the idea of their equality.

Grade: 9-12| ©2004, PBS.

L.

Searching for a New Home in the American West [04:20] (Downloaded

from

Learn360)

A clip from the full video: The Unfinished Nation-The Meeting Ground

A brief look at the desire of newly freedmen to move west, and the struggles they encounter through the

many white immigrants also taking advantage of the Homestead Act.

Grade: 9-12| ©2004, Intelecom.

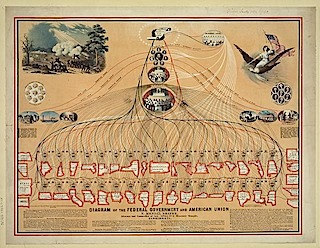

M. Diagram of the Federal Government and

American Union by N. Mendal Shafer,

attorney and counseller at law, office no. 5 Masonic

Temple, Cincinnati

-

Illustrates the intertwined nature of the American republic

N. What a Colored Man Should do to Vote

(Pamphlet)

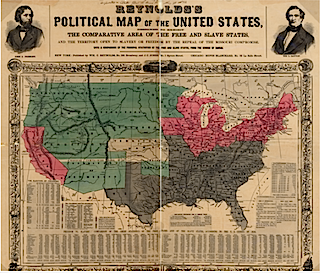

O. Reynolds's political map of the United States

-

Demonstrates the area of the free and slave states

Procedures/Culminating Activities:

H-1:

Students will have read text account of Reconstruction.

Day 1: Students will be provided projection of the summaries of the major Reconstruction plans, and will be provided a position within the scope of Reconstruction. Video clip providing general information on Reconstruction will be viewed and discussed as a class. Readings will be posted online for students to read on their own prior to day 2.

Day 2:

Class will meet in the computer lab to continue research on their position

regarding Reconstruction. Of the

resources provided (video clips, readings, documents, visuals, etc.) students

will investigate and gather information to strengthen their position regarding

Reconstruction. They may also

research for their own two (2) resources to aid in their arguments.

Day 3: In

class, students will propose, argue, and defend their Reconstruction

positions. This will continue for

a maximum of 3 class periods depending on student engagement.

Resource B. (Each group will only

need to read one section, they can read the others)

Lincoln’s Ten-Percent Plan:

1863–1865

After

major Union victories at the battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg in 1863,

President Abraham Lincoln began preparing his plan for Reconstruction to

reunify the North and South after the war’s end. Because Lincoln believed that

the South had never legally seceded from the Union, his plan for Reconstruction

was based on forgiveness. He thus issued the Proclamation of Amnesty and

Reconstruction in 1863 to announce his intention to reunite the once-united

states. Lincoln hoped that the proclamation would rally northern support for

the war and persuade weary Confederate soldiers to surrender.

The

Ten-Percent Plan

Lincoln’s

blueprint for Reconstruction included the Ten-Percent Plan, which specified

that a southern state could be readmitted into the Union once 10 percent of its

voters (from the voter rolls for the election of 1860) swore an oath of

allegiance to the Union. Voters could then elect delegates to draft revised

state constitutions and establish new state governments. All southerners except

for high-ranking Confederate army officers and government officials would be

granted a full pardon. Lincoln guaranteed southerners that he would protect

their private property, though not their slaves. Most moderate Republicans in

Congress supported the president’s proposal for Reconstruction because they

wanted to bring a quick end to the war.

In

many ways, the Ten-Percent Plan was more of a political maneuver than a plan

for Reconstruction. Lincoln wanted to end the war quickly. He feared that a

protracted war would lose public support and that the North and South would

never be reunited if the fighting did not stop quickly. His fears were

justified: by late 1863, a large number of Democrats were clamoring for a truce

and peaceful resolution. Lincoln’s Ten-Percent Plan was thus lenient—an attempt

to entice the South to surrender.

Lincoln’s

Vision for Reconstruction

President

Lincoln seemed to favor self-Reconstruction by the states with little

assistance from Washington. To appeal to poorer whites, he offered to pardon

all Confederates; to appeal to former plantation owners and southern

aristocrats, he pledged to protect private property. Unlike Radical Republicans

in Congress, Lincoln did not want to punish southerners or reorganize southern

society. His actions indicate that he wanted Reconstruction to be a short

process in which secessionist states could draft new constitutions as swiftly

as possible so that the United States could exist as it had before. But

historians can only speculate that Lincoln desired a swift reunification, for

his assassination in 1865 cut his plans for Reconstruction short.

Louisiana

Drafts a New Constitution

White

southerners in the Union-occupied state of Louisiana met in 1864—before the end

of the Civil War—to draft a new constitution in accordance with the Ten-Percent

Plan. The progressive delegates promised free public schooling, improvements to

the labor system, and public works projects. They also abolished slavery in the

state but refused to give the would-be freed slaves the right to vote. Although

Lincoln approved of the new constitution, Congress rejected it and refused to

acknowledge the state delegates who won in Louisiana in the election of 1864.

The

Radical Republicans

Many

leading Republicans in Congress feared that Lincoln’s plan for Reconstruction

was not harsh enough, believing that the South needed to be punished for

causing the war. These Radical Republicans hoped to control the Reconstruction

process, transform southern society, disband the planter aristocracy,

redistribute land, develop industry, and guarantee civil liberties for former

slaves. Although the Radical Republicans were the minority party in Congress,

they managed to sway many moderates in the postwar years and came to dominate

Congress in later sessions.

The

Wade-Davis Bill

In

the summer of 1864, the Radical Republicans passed the Wade-Davis Bill to counter Lincoln’s Ten-Percent Plan. The bill

stated that a southern state could rejoin the Union only if 50 percent of its

registered voters swore an “ironclad oath” of allegiance to the United States.

The bill also established safeguards for black civil liberties but did not give

blacks the right to vote.

President

Lincoln feared that asking 50 percent of voters to take a loyalty oath would

ruin any chance of ending the war swiftly. Moreover, 1864 was an election year,

and he could not afford to have northern voters see him as an uncompromising

radical. Because the Wade-Davis Bill was passed near the end of Congress’s

session, Lincoln was able to pocket-veto it, effectively blocking the bill by

refusing to sign it before Congress went into recess.

The

Freedmen’s Bureau

The

president and Congress disagreed not only about the best way to readmit

southern states to the Union but also about the best way to redistribute

southern land. Lincoln, for his part, authorized several of his wartime

generals to resettle former slaves on confiscated lands. General William Tecumseh

Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15 set aside land in South Carolina and

islands off the coast of Georgia for roughly 40,000 former slaves. Congress,

meanwhile, created the Freedmen’s Bureau in early 1865 to distribute food and

supplies, establish schools, and redistribute additional confiscated land to

former slaves and poor whites. Anyone who pledged loyalty to the Union could

lease forty acres of land from the bureau and then have the option to purchase

them several years later.

The

Freedmen’s Bureau

The

Freedmen’s Bureau was only slightly more successful than the pocket-vetoed

Wade-Davis Bill. Most southerners regarded the bureau as a nuisance and a

threat to their way of life during the postwar depression. The southern

aristocracy saw the bureau as a northern attempt to redistribute their lands to

former slaves and resisted the Freedmen’s Bureau from its inception. Plantation

owners threatened their former slaves into selling their forty acres of land,

and many bureau agents accepted bribes, turning a blind eye to abuses by former

slave owners. Despite these failings, however, the Freedman’s Bureau did

succeed in setting up schools in the South for nearly 250,000 free blacks.

Lincoln’s

Assassination

At

the end of the Civil War, in the spring of 1865, Lincoln and Congress were on

the brink of a political showdown with their competing plans for

Reconstruction. But on April 14, John Wilkes Booth, a popular stage actor from

Maryland who was sympathetic to the secessionist South, shot Lincoln at Ford’s

Theatre in Washington, D.C. When Lincoln died the following day, Vice President

Andrew Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee, became president.

Andrew Johnson,

Laissez-Faire, and States’ Rights

Johnson,

a Democrat, preferred a stronger state government (in relation to the federal

government) and believed in the doctrine of laissez- faire , which stated that

the federal government should stay out of the economic and social affairs of

its people. Even after the Civil War, Johnson believed that states’ rights took

precedence over central authority, and he disapproved of legislation that

affected the American economy. He rejected all Radical Republican attempts to

dissolve the plantation system, reorganize the southern economy, and protect

the civil rights of blacks.

Although

Johnson disliked the southern planter elite, his actions suggest otherwise: he

pardoned more people than any president before him, and most of those pardoned

were wealthy southern landowners. Johnson also shared southern aristocrats’ racist

point of view that former slaves should not receive the same rights as whites

in the Union. Johnson opposed the Freedmen’s Bureau because he felt that

targeting former slaves for special assistance would be detrimental to the

South. He also believed the bureau was an example of the federal government

assuming political power reserved to the states, which went against his

pro–states’ rights ideology.

Like

Lincoln, Johnson wanted to restore the Union in as little time as possible.

While Congress was in recess, the president began implementing his plans, which

became known as Presidential Reconstruction. He returned confiscated property

to white southerners, issued hundreds of pardons to former Confederate officers

and government officials, and undermined the Freedmen’s Bureau by ordering it

to return all confiscated lands to white landowners. Johnson also appointed

governors to supervise the drafting of new state constitutions and agreed to

readmit each state provided it ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, which

abolished slavery. Hoping that Reconstruction would be complete by the time

Congress reconvened a few months later, he declared Reconstruction over at the

end of 1865.

The

Joint Committee on Reconstruction

Radical

and moderate Republicans in Congress were furious that Johnson had organized

his own Reconstruction efforts in the South without their consent. Johnson did

not offer any security for former slaves, and his pardons allowed many of the

same wealthy southern landowners who had held power before the war to regain

control of the state governments. To challenge Presidential Reconstruction,

Congress established the Joint Committee on Reconstruction in late 1865, and

the committee began to devise stricter requirements for readmitting southern states.

The

Northern Response

Ironically,

the southern race riots and Johnson’s “Swing Around the Circle” tour convinced

northerners that Congress was not being harsh enough toward the postwar South.

Many northerners were troubled by the presidential pardons Johnson had handed

out to Confederates, his decision to strip the Freedmen’s Bureau of its power,

and the fact that blacks were essentially slaves again on white plantations.

Moreover, many in the North believed that a president sympathetic to southern racists

and secessionists could not properly reconstruct the South. As a result,

Radical Republicans overwhelmingly beat their Democratic opponents in the

elections of 1866, ending Presidential Reconstruction and ushering in the era

of Radical Reconstruction.

Radical Reconstruction:

1867–1877

After

sweeping the elections of 1866, the Radical Republicans gained almost complete

control over policymaking in Congress. Along with their more moderate

Republican allies, they gained control of the House of Representatives and the

Senate and thus gained sufficient power to override any potential vetoes by

President Andrew Johnson. This political ascension, which occurred in early

1867, marked the beginning of Radical Reconstruction (also known as Congressional

Reconstruction).

The

First and Second Reconstruction Acts

Congress

began the task of Reconstruction by passing the First Reconstruction Act in

March 1867. Also known as the Military Reconstruction Act or simply the

Reconstruction Act, the bill reduced the secessionist states to little more

than conquered territory, dividing them into five military districts, each

governed by a Union general. Congress declared martial law in the territories,

dispatching troops to keep the peace and protect former slaves.

Congress

also declared that southern states needed to redraft their constitutions,

ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, and provide suffrage to blacks in order to

seek readmission into the Union. To further safeguard voting rights for former

slaves, Republicans passed the Second Reconstruction Act, placing Union troops

in charge of voter registration. Congress overrode two presidential vetoes from

Johnson to pass the bills.

Reestablishing

Order in the South

The

murderous Memphis and New Orleans race riots of 1866 proved that Reconstruction

needed to be declared and enforced, and the Military Reconstruction Act

jump-started this process. Congress chose to send the military, creating

“radical regimes” throughout the secessionist states. Radical Republicans hoped

that by declaring martial law in the South and passing the Second

Reconstruction Act, they would be able to create a Republican political base in

the seceded states to facilitate their plans for Radical Reconstruction. Though

most southern whites hated the “regimes” that Congress established, they proved

successful in speeding up Reconstruction. Indeed, by 1870 all of the southern

states had been readmitted to the Union.

Radical

Reconstruction’s Effect on Blacks

Though

Radical Reconstruction was an improvement on President Johnson’s laissez-faire Reconstructionism,

it had its ups and downs. The daily lives of blacks and poor whites changed

little. While Radicals in Congress successfully passed rights legislation,

southerners all but ignored these laws. The newly formed southern governments

established public schools, but they were still segregated and did not receive

enough funding. Black literacy rates did improve, but marginally at best.

The

Tenure of Office Act

In

addition to the Reconstruction Acts, Congress also passed a series of bills in

1867 to limit President Johnson’s power, one of which was the Tenure of Office

Act. The bill sought to protect prominent Republicans in the Johnson

administration by forbidding their removal without congressional consent.

Although the act applied to all officeholders whose appointment required

congressional approval, Republicans were specifically aiming to keep Secretary

of War Edwin M. Stanton in office, because Stanton was the Republicans’ conduit

for controlling the U.S. military. Defiantly, Johnson ignored the act, fired

Stanton in the summer of 1867 (while Congress was in recess), and replaced him

with Union general Ulysses S. Grant. Afraid that Johnson would end Military

Reconstruction in the South, Congress ordered him to reinstate Stanton when it

reconvened in 1868. Johnson refused, but Grant resigned, and Congress put Edwin

M. Stanton back in office over the president’s objections.

Resource M.

http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/ampage?collId=rbaapc&fileName=33200/rbaapc33200.db&recNum=0&itemLink=D?rbaapcbib:2:./temp/~ammem_AqQQ::&linkText=0

http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/ampage?collId=rbaapc&fileName=33200/rbaapc33200.db&recNum=0&itemLink=D?rbaapcbib:2:./temp/~ammem_AqQQ::&linkText=0

Resource O.

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/map_item.pl

(zoom in using electronic version)