|

Sentence TypesThere are three basic principles that English teachers use to categorize sentences: 1) End Point Punctuation, 2) Main Verb Type, and 3) Sentence Complexity. The exercises just completed demonstrate these three principles in order. When the principle of end point punctuation is used, the focus is placed on rendering spoken language into written form, especially in ways to capture intonation patterns. When the principle of main verb type is used, the focus is on recognizing sentence patterns, including the positions of words in a sentence as well as the grammatical and semantic roles of the words in the sentence. When the principle of sentence complexity is used, the focus is on the variety of transformations speakers and writers engage in as they creatively use language, especially as they alter the basic sentence in order to relate one thought or sentence to another across a stretch of discourse. Most native speakers encounter lessons based on all these principles at some point in school. End point punctuation When sentences are categorized by end point punctuation, three groups are created:

End point punctuation actually attempts to encode a speaker’s intonation with a written symbol, and each end point is associated with a specific intonation pattern. The focus on end point punctuation generally comes in writing or composition classes, and looking at sentences in this way may also be useful when teaching students to read dialog in narrative literature (novels, short stories, plays). Classically, a period is used at the end of a declarative statement. The spoken intonation pattern that is captured with a period is an overall downward turn of pitch across the whole utterance. Pitch will rise to some extent on the stressed syllables within each word in the sentence, but overall, when a speaker makes a statement with a generally downward pitch, it is rendered into written form with a period to mark the end of the utterance.

Fig. 7: Intonation pattern of a declarative sentence A question mark is used to indicate an utterance with a generally rising intonation pattern across the entire utterance. Even when the subject-auxiliary inversion that co-marks a question is absent, rising intonation alone can indicate a questioning orientation, and such an utterance is marked with a question mark. Classically, yes-no questions carry the general rise across the entire utterance, although wh- questions generally rise and then fall sharply on the final syllable. The question mark is still used for wh-questions as they still tend to rise in intonation across the whole before finally falling.

Fig 8: Yes-No Question Intonation Pattern

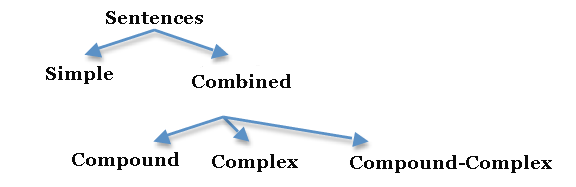

Fig 9: Wh- Question Intonation Pattern An exclamation point is used to mark any utterance that is accompanied by a high level of emotion, no matter whether that emotion is excitement or distress. In general, utterances marked by high emotion are marked with increased loudness as well as higher pitch, and the exclamation point is used to capture the increased pitch and volume. The categorization of sentences by end point punctuation, then, really captures the sector where meaning and use overlap in the tripartite view of language dimensions. To wit, when a speaker forms a sentence with a falling intonation pattern and writes a representation of that sentence ending it with a period, the speaker uses that structure to indicate the presentation of information. When a speaker uses a rising intonation pattern and writes a representation of that sentence ending it with a question mark, the speaker is seeking information. When a speaker increases both the pitch and the volume of an utterance and represents that sentence in writing with an exclamation point, the speaker is expressing a high level of emotion over the either the content or situation of the utterance. Main verb The verb is considered the center of the English sentence. Linguists often break the verb down further and state that the tense or mood of the verb is the true center, but since the tense and mood are caught up into the verb form itself, it is not entirely inaccurate to say that the verb is the center. Because the verb is the center, then, it only makes sense to group sentences into types based on the type of verb that forms the center of the whole. When this is done, we get a series of sentence patterns, all determined by whether the main verb is an action verb or a linking verb and the further subdivisions of these two types of main verbs. The details of these various patterns include the familiar features of direct objects, indirect objects, predicate nominatives and predicate adjectives, to name a few. The categorization of sentences by main verb type captures the sector where form and use overlap in the tripartite view of language dimensions. Direct object and indirect object are the names of two specific grammatical roles. Closer study of verb types and the sentence patterns that result will be taken up later in this chapter and in the unit on verbs. Sentence Complexity Some sentences consist of just one subject-predicate pairing, and these sentences are called simple sentences. Traditionally, these one subject-predicate pairings are called independent clauses and are further defined as “able to stand alone.” This definition is presented to young learners to assist them in distinguishing a simple sentence from partial sentences that in spoken language form complete utterances, such as “Because I said so,” which can be the totality of a response to a child’s why question. The explanation is that the “because” utterance can’t be said just right off the bat in a conversation, but has to attach meaning-wise to what just came before it. Other sentences have more than one subject-predicate pairing combined together, and these sentences are given various names according to the relationships between the two (or more) clauses. If the two clauses are essentially equal to each other, then the sentence is a compound sentence. If one sentence plays a grammatical role (acts as a direct object, for example, or acts as an adverb) for the other, then that clause is a subordinate clause, and the sentence is considered a complex sentence. A sentence that has a minimum of three clauses, two of which are equals and one which plays a grammatical role for one of those two, is called a compound-complex sentence. These terms and their definitions are often presented in elementary or middle school in the U.S., and that’s why they are included here. The term compound-complex seems to be falling out of use in recent years, however. A more useful approach, in my opinion, is the addition of another level to the categories and subcategories of complexities; distinguishing first between sentences that have only one subject-predicate pairing (one clause)—the simple sentence, and those that have more than one pairing (more than one clause)—the combined sentence. After the counting of clauses is done, then the issue of how the clauses in combined sentences relate to each other can be taken up and labeling of those subcategories of combined sentences can take place. We might think of sentences categorized by this principle in this way: Sentences:

Or a more visual representation might be:

Fig. 10: Categories and subcategories of sentence complexity The categorization of sentences by sentence complexity can be seen roughly as corresponding to the sector of overlap between meaning and form because a subordinate clause can play a grammatical role for the main (independent) clause to which it is attached, but that’s a little too neat for reality. This focus, too, carries an aspect that can place it into the form-use overlap—dependence and independence of clauses reflects a speaker’s desire to subordinate one idea to another or not, and thus to affect a listener’s way of thinking about the same ideas. |