JULIUS

AND MOSES STERN:

WHEN TIME RAN OUT

|

Every one of Herman Stern's brothers had served in the German Army during World War I, which helps to explain why they hesitated to leave Germany. For the time the Nazis paid at least a small amount of respect to Jewish veterans of the Great War. (a) So it is not surprising that several of these veterans assumed that the anti-Semitic activities of Hitler's government would not extend to them. Some Jewish veterans organizations continued to pledge their support to Hitler's government. Then, in November 1935, the government issued a decree that stated "A Jew cannot be a citizen of the Reich,"and announced that all restrictions on Jews in Germany would now apply to Jewish military veterans as well.

This shocked some of Herman's brothers into reconsidering their futures. His brother Gustav (b), having sent his children Erich and Klara to America in 1934, decided to leave Germany at least two months before the Reich's action in November 1935. Gustav's wife Selma wrote to Herman that September that they were already obtaining papers to leave from the German government. They were in fact so confident that the process of immigration could be taken care of quickly that Selma asked about her furniture: "If Gustav and I go to work, does one rent a furnished room or an empty apartment [in America]? One does not get much for used furniture, secondly, there is an oversupply of older goods, because of so many emigrating families."

Alas, Gustav and Selma learned that they would not be going anywhere soon. The American consulate in Stuttgart rejected their applications for visas on health grounds: Gustav had once consulted a heart specialist in Germany. It took Gustav, with Herman also writing letters to Washington, almost three years to satisfy the State Department that this was a routine medical matter and he did not have a heart condition. Gustav was further annoyed when the Stuttgart consulate insisted he file completely new sets of papers for another visa application. "The consulate people are very busy and generally rather sharp, so that a more detailed conversation [of our situation] is totally impossible," he wrote Herman in 1938. "I had written a lengthy detailed letter to the consul and mentioned to him that it is not right to require the documents a second time. Up to today, no answer or reaction whatsoever." Indeed they would not leave Germany until 1939, and then for South America instead of the United States. They did not get permission to live in America until several more months had passed.

Gustav was seven years older than Herman and was his youngest brother. So the delays that he endured to get to the United States were comparatively mild than those of Herman's older brothers, Julius, who was 60 in 1937, and Moses, who was 65. Both Moses and Julius hesitated to leave Germany, with Julius telling his niece Lotte Henlein, "Where else would life be as fine as in Germany?" After the shock of Kristallnacht in 1938, however, they became more willing to heed the pleas of relatives to leave and asked their brother Herman to see if he could arrange.

Herman was, as ever, resourceful. He persuaded a farmer near Valley City to sign a pledge to hire both brothers, and asked the State Department for visas for Moses, Julius, and Julius's wife Frieda. (c) But the Federal Government moved very slowly on these applications, and the outbreak of war in 1939 made communications even more difficult (see the letter from Herman Stern to the American consulate, above). The State Department did finally grant visas for Moses, Julius, and Frieda early in 1941. By then, however, it was enormously difficult for anyone in Europe to book passage on a ship to America. Many ship tickets sold at enormously inflated prices; counterfeit tickets circulated freely and bribery was not uncommon in obtaining even these. Herman deposited some of money with the Joint Distribution Committee in New York in order to put his brothers in line for tickets. But but then he had been unable to contact them for months and could only hope for the best.

Those hopes proved to be futile. The Sterns learned nothing of the fate of Moses, Julius or Frieda until after the war, then learned that they had all died. The official history of Oberbrechen, Germany, indicates that Moses died in "Ghetto Theresienstadt" in Czechoslovakia, in October 1942. Julius and Frieda had died, apparently in 1943, in or another of the concentration or death camps. Herman had helped to bring dozens of Germans Jews to America, but his inability to snatch Moses and Julius and his wife from the maw of the Holocaust bothered him ever after.

|

|

|

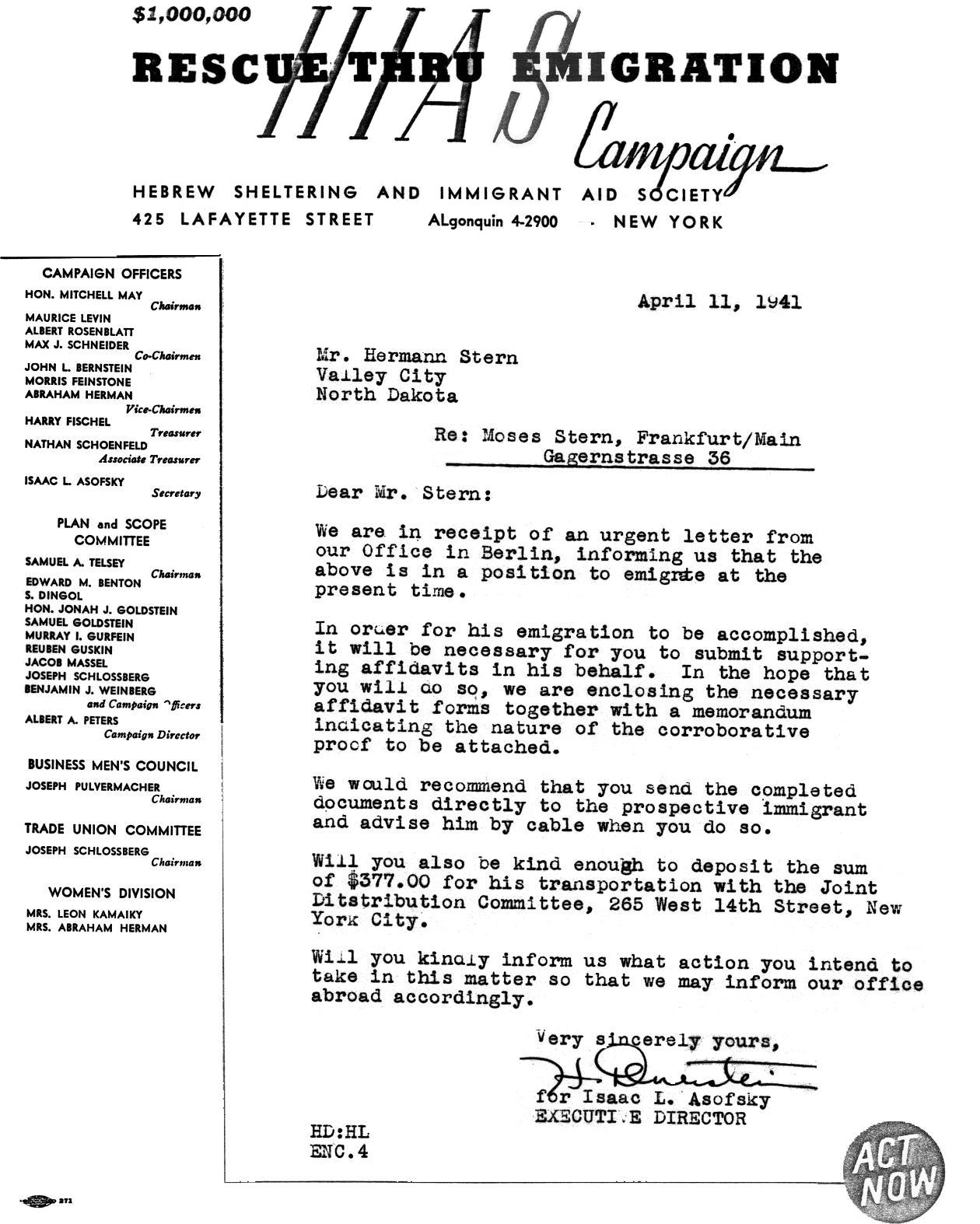

Letter to Herman Stern from HIAS regarding Moses Stern's visa. |

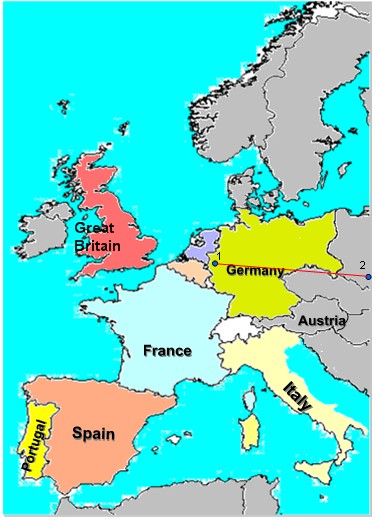

After 3 years of effort to obtain visas for the United States, Moses Stern, his brother Julius and Julius's wife Frieda were taken from their home near Oberbrechen (1) and sent to camps in the east (2), where they died. |

Documents on this page courtesy of Herman Stern Papers, OGL#217, Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections, Chester Fritz Library, University of North Dakota.